Earlier this year, Waag Futurelab launched the Mobifree project together with partners. The mission is as ambitious as it is fundamental: to provide European residents and organisations with greater choice and access to human-centric and ethical mobile software. Danny Lämmerhirt leads this journey for Waag. He explains why mobile software is so crucial, how it is now dominated by two big players and why we need to invest in alternatives.

Mobifree talks about the 'mobile ecosystem'. That sounds like something really big. What should we mean by this? 'The mobile ecosystem is indeed a vast collection of interacting components on your smartphone. This includes things like your apps, the phone itself (hardware), the operating system, the connections to the cloud, the firmware, the interfaces through which apps and other code communicate with each other, and all the data that flows between these parts. In Mobifree, we look at all these layers of the mobile ecosystem. Now, important parts of the system are controlled by Apple and Google, leading to all kinds of unwanted dependencies and problems. Our goal is to provide an alternative.'

Most mobile phones have an Android (Google) or IOS (Apple) operating system. What is problematic about that? 'Globally, about 99% of all smartphones are controlled by an Android system (about 70%) or iOS (about 30%) including associated app databases: Google Play & App Store. This market dominance creates several problems. For instance, Apple centralises the development of its iOS within their own walls, thereby controlling app development. Android, on the other hand, was open-sourced from the start, in order to distribute the system faster. That sounds good, but the most widely used versions of Android, such as Samsung's, have all kinds of closed apps from Samsung, Google and others companies pre-installed. Users often cannot uninstall these apps, and research shows that all kinds of data is shared by these applications. This puts both users freedom of choice and data protection under pressure. In addition, until recently, the only option for users was to use Apple's App Store and Google's Playstore to install apps. This is an unprecedented concentration of power. Imagine if all the supermarkets in the world were either an Albert Heijn or a Jumbo. That’s the choice you have. Then two companies decide what products go into the market, the quality standards, the price - the whole chain.'

Imagine if all the supermarkets in the world were either an Albert Heijn or a Jumbo. That’s the choice you have.

So, they make phones and operating systems, but what does that have to do with applications? Surely anyone can develop and market an app? 'That's right. But these two Silicon Valley profit-driven companies decide which apps are or are not allowed, and moderate what our mobile software looks like. Also, the commission they skim off on paid apps is so large that it is not profitable for many independent app builders to invest in them. New legislation like the Digital Markets Act is going to change that, but we have yet to see the effects.

Another problem is moderation. The quality criteria of apps are determined by Apple and Google. After all, they determine which apps are and are not allowed in their app stores. This also applies to medical and health apps. Ideally, for this kind of sensitive information, you would want professional medical institutions to assess whether apps are medically sound or not. This role now lies with Google and Apple. As a result, health institutions struggle with health apps and information in them, which they cannot get a grip on, with all the medical consequences that entails.'

If we solve the moderation problem, we fix the entire thing? 'No, unfortunately not. Another problem is that apps need to be linked to operating systems. That means apps need certain 'iOS drivers' to function. So, the app has to be able to 'talk' to Apple's system. But to access those drivers, the app must be distributed through the App Store, and that forces app developers to consent to Apple's privacy terms. A clever ploy to stay within Apple's sphere of influence.

With Google, it is a similar story. Developers who distribute their apps on the Google Play store also use Google Play Services. That is a set of code that Google offers to developers to more easily integrate features into their apps, such as Google Maps or Google Analytics. With this convenience also comes a dependency. Apps developed for Android cannot use many system features without Google Play Services. And through Play Services, a lot of data about your app usage, identification numbers of your device, and other individual user data are shared with Google. Apps themselves must be honest with their users about what data they collect. But the mandatory connection to Google Play Services to use system features to make the app work remains hidden under the hood.'

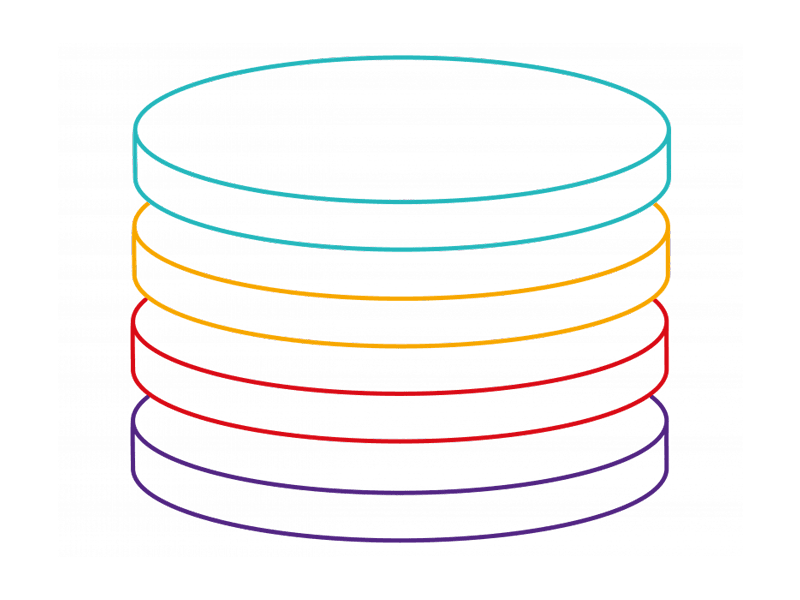

This means that they really control everything? You can put it that way. It practically means that two parties control crucial places in your phone's 'technology stack'. That sounds complicated, but boils down to the following. Every mobile ecosystem is a combination of different parts: think of your operating system (iOS/Android), your apps (Whatsapp/Google Maps), your cloud service (Drive/iCloud), your internet browser (Chrome/Safari) and your device (e.g. Samsung or Huawei phones/iPhone). Google and Apple control large parts of this stack. This is problematic. At Waag we have the ambition to work towards a ‘public stack’, with layers that are based on public-, instead of shareholders values.’

Can you cite an example when that causes problems? 'During the COVID-19 pandemic, the government developed an app that collected location data from users to see if you had been near infected people and thus needed to be isolated. This is where governments really became dependent on the mobile infrastructure of two big companies - and forced citizens to become part of it.

Another frightening example was uncovered by the Electronic Frontier Foundation and Mozilla Foundation. Their research found that several menstrual apps were collecting and sharing data with advertisers. Data that, researchers warned, could even be requested by law enforcement officials in US states where abortion is not allowed. You have 'nothing to hide', until data about your menstrual cycle suddenly takes on legal context. It is very disturbing that this kind of data can be collected and shared. Even worse, these apps are simply available for download in the app stores, without alerting users to the possible consequences.

You have 'nothing to hide', until data about your menstrual cycle suddenly takes on legal context.

This also shows a kind of hypocrisy of the idea of consent. App stores and apps only communicate certain data streams exchanged between apps and other technologies, like when you share location or activity data between a health app and an app like Strava. This type of data flow is governed by so-called 'permissions', which are defined by Google and Apple. But tracker data is not covered by these. That means Apple and Google determine which data streams you have control over. You have control over some data exchanges, but far from all of them.

Think again about those supermarkets again. Our food in supermarkets is strictly controlled for health risks by the Dutch Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority, among others. But who controls our app stores and our digital ecosystem?'

Are there other app stores that can offer an alternative? 'In Mobifree, we work with a large number of partners with a lot of experience in this field. NLnet has been investing in an open and secure internet for years. F-Droid is developing a digital library for free and open source mobile software. So that app store without Google and Apple is already there! We also want to spread the word: there are alternatives. For example, the F-Droid app store has an automatic scanner, which reads the source code and sees if there are hidden data leaks in apps. Thus, this scanner filters out the 'wrong' apps in advance. F-Droid calls this 'antifeatures'. The E-Foundation is also involved in this project. With their own operating system E/OS, they are working on a 'deGoogled' smartphone. This deGoogled operating system offers features similar to Android, as we are also working with microG. MicroG has been offering an alternative to Google Play Services for years, so apps are not forced to use Google's interfaces to be smart. They also see more and more users who have looked critically 'under the hood of their smartphones and want to get rid of Google and Apple immediately. With the partners within Mobifree, this puts us in a unique company of experts who not only share our problem analysis, but are already working on the alternatives at all layers of the mobile ecosystem. That this community has already grown so much gives hope for the future.'

The app store without Google and Apple is already there!

In the study, you also look at specific target groups of such an ethical and open source app store. For whom is this particularly interesting and urgent at the moment? 'We are working with different test groups, but two that stand out are humanitarian aid workers and civil servants. That first group is interesting because they provide assistance to the most vulnerable people in difficult circumstances. This often happens in the context of politically unstable or hostile regimes. Access to mobile software where these regimes cannot look over your shoulder is then sometimes a matter of life and death. This target group in particular can teach us a lot about how to design a secure mobile ecosystem. For civil servants and politicians, researching alternatives is also an urgent topic. On the one hand, because they do their work based on public values and serving public cause, but also because they struggle with apps on their own phones. For instance, Dutch government banned a dozen apps on civil servants' phones, but State Secretary van Huffelen (Digital Affairs) allows those same civil servants to use commercial cloud services. An interesting dilemma from which we can hopefully learn a lot.'

What can we expect in the near future? 'If you want to tackle the digital mobile ecosystem, you have to work with several components. We are working on further developing operating systems and investing in apps and developers of human-centric and ethical mobile software. We are also continuing to build an app store based on public with F-Droid and microG. And all this in close contact with various user groups. In this way, we hope to make strides on both the demand and supply side. In this way, we want to develop and strengthen European value-driven and public alternatives. Only then can we phase out our dependence on the commercial Silicon Valley data hungry, or the state-driven Chinese tools, and truly establish and flourish a European digital public space.'

In this way, we want to develop and strengthen European value-driven and public alternatives.

Can people also participate? 'Definitely. We have just started organising workshops with users. Besides humanitarian aid workers and civil servants, we also want to involve young adults and app developers. If they are interested, I would like to invite them to join us.'

Do you want to participate? Mail to aris (at) waag (dot) org

Want to stay informed? Sign up for the newsletter or follow us on Mastodon or LinkedIn.