The Social Tech Tour is a series of site visits to innovative, tech-enabled social enterprises. The main objective is a peer learning: letting innovators and practitioners learn from each other. Every edition, hosts and participants will co-create a roadmap on one particular real-life challenge.

The first stop of the Social Tech Tour brought us to OneFarm at A Lab in the North of Amsterdam. Twenty-three participants joined the fully booked event, coming from a wide range of fields including agriculture, architecture, social entrepreneurship, digital media, engineering and the circular economy, to name a few.

Vertical farming

OneFarm and their approach to vertical farming is a possible solution to urban food security issues and to climate challenges aggravated by (industrial) farming. Critics point out the immense investment needed to technically execute vertical farming and the risk of misalignment between societal needs and the benefits of innovations in farming. This is because vertical farms often produce high-value products that tend to serve the wealthiest segment of the consuming public. On the other hand, supporters emphasise the positive aspects of vertical farming, like the omission of pesticides, the use of up to 99% less water, higher yields and faster growth, improved food quality and year-round nutrition, as well as more localised production which reduces transport needs.

Jan Feist, project manager and plant enthusiast at OneFarm, gave a tour of the showroom containing lettuce and plant-based pharmaceuticals in different growth stages, followed by a presentation offering insights into the technical, financial and practical aspects of large-scale vertical farming in a city like Amsterdam.

Co-creation workshop

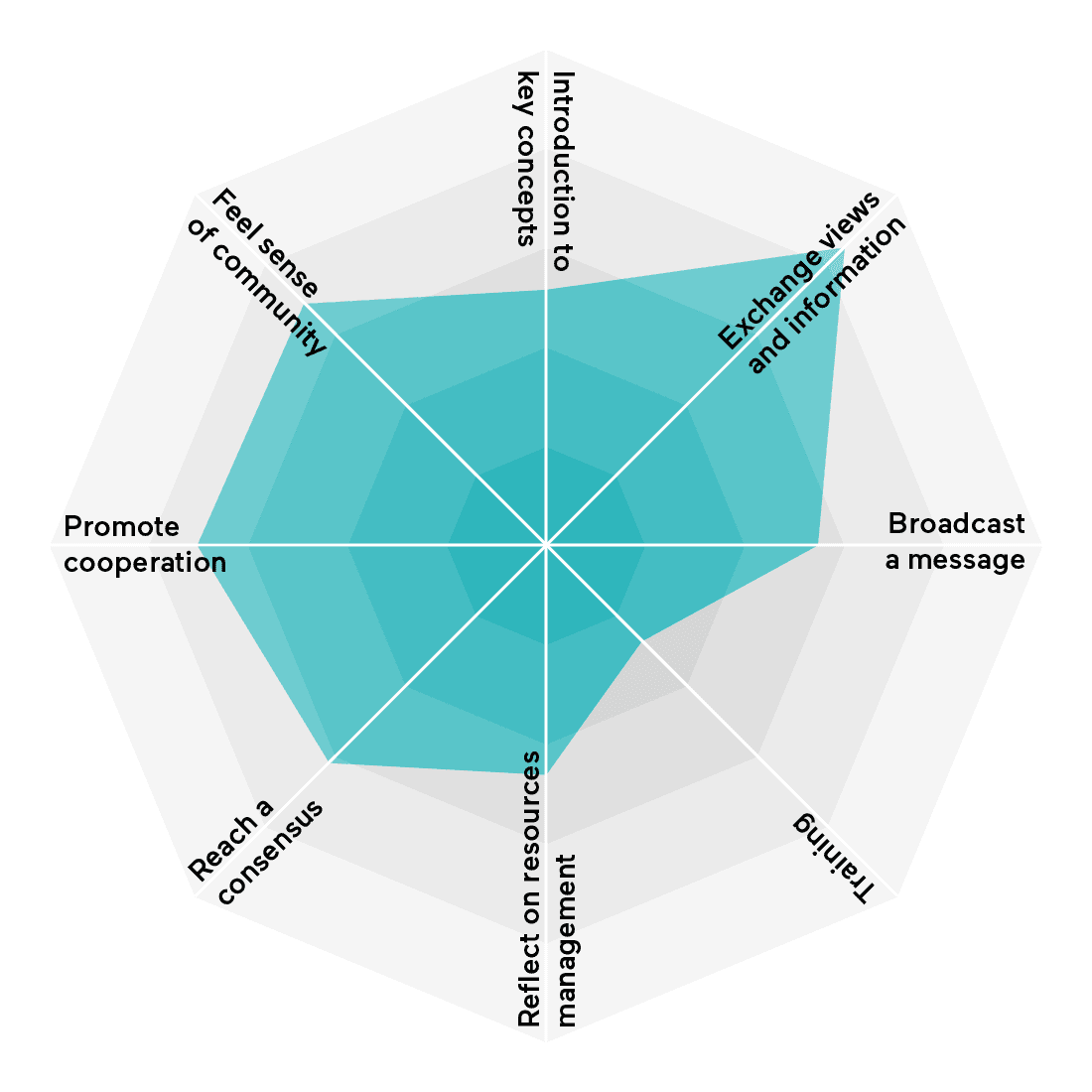

Following the tour, four groups of participants joined a two hour co-creation workshop, during which they brainstormed and developed ideas for innovative, tech-enabled food production initiatives.

The initiatives were based on technologies ranging from mobile applications ( such as "Mobile farm" and "Adopt a salad") to neighbourhood-based cooperative farms (such as "Cooperative supermarket 2.0"), to a state-of-the-art tailor-made integration of a circular food system into the urban fabric ("Vertical circle"). For example, the online application "Adopt a salad" introduces some sort of motherhood into the care-taking of a salad. Similar to the Tamagotchi from the 1990s, each person is responsible for taking care and following the growth of his or her own produce. The aim would be to educate people on the true cost and production process behind farming and to involve a long-term nurturing of local vertical farms.

Interestingly enough, the learning attribute finds consideration in all four concepts. By involving citizens through a game like Tamagotchi or collaborating with schools as proposed in “Vertical circle”, urban food systems may not only promote a healthy lifestyle, but can also be leveraged to involve the community in the production choices that simultaneously carry responsibility for the environment.

The community aspect found in all four concepts emphasizes this as well. The participants agreed to find a solution on the local level with the neighbours being the main stake- and shareholders, followed by local businesses, the local government and real estate owners. Be it through neighbourhood harvest activities, communal dinners or the local exchange of food, participants argued that any urban food system should also aim to strengthen social ties. The "Mobile farm" for instance, an application that serves as a virtual exchange vehicle for the trading of food on the neighbourhood level, engages consumers and producers through word by mouth and a pilot in one street.

Another striking aspect is the value of high quality produce. In the concepts ideated by co-creation participants, healthy produce is not merely measured in financial terms but can also be traded with food, fertilizer, a service like farming or time (as proposed in "Mobile farm" and "Cooperative supermarket 2.0"). In terms of the economic system to ensure long-term viability, the equal value of money and time allows for positive effects in socio-economic terms. This means that if someone does not have the financial means to buy quality food, the possibility to trade one’s time or another service would instead guarantee equal access to a healthy diet.

"Vertical circle" took this idea one step further: The foundation is based on partnerships, through which the urban food cycle is closed in a sustainable manner. Based on a token-based reward system, an urban vertical farm can collaborate with local businesses like an anaerobic digestion company that provides fertilizers, a bicycle waste collection and produce distribution service and schools to offer educational possibilities. Admitting that this is a major logistical challenge, the concept would require a well-developed integration into an existing urban fabric. In Amsterdam, this fabric already exists, and further support by the local government would be in line with the municipality’s sustainability agenda.

Lessons learned

There is, on the one hand, an increased demand for sustainable produce as well as cutting-edge technologies in farming. On the other hand, there is a lack of awareness on how to execute these ideas on a large scale and in a sustainable manner. The ideas collected during our co-creation workshop show that any tech-enabled food production aimed at facilitating environmentally friendly local food production should also include the involvement of local communities. By turning the “normal” consumer into the main shareholder, educator and producer— and to do so through local farming activities, online applications, the collaboration with schools or other citizen engagement exercises like co-creation methods—, new possibilities arise regarding learning and the development of a consciousness for what we eat and where it comes from.

Another important point made is that there is no need to reinvent the wheel: many existing structures are already built into the fabric of a city like Amsterdam, meaning that the main challenge is to alter the stream of resources (produce, waste, fertilizers, etc.) on a more local level. This can be supplemented through innovative farming concepts like vertical farms. With the benefit of quality produce, the community seems to be on board.

It comes at no surprise that the ideas gathered throughout the workshop do not offer ready-made solutions and strategies for overcoming environmental issues caused by traditional industrial agriculture. Rather, the workshop aimed to stimulate the entrepreneurial spirit of citizens, consumers and practitioners in the collaborative action that are necessary to find the right solutions. Thus, the workshop did not only compress the social and tech expertise of those present, but also highlighted the variety of questions that still need to be answered in the search of the 21st century form of food production.

What is missing to scale-up the vertical farm concept? A viable business plan, technological process or the inclusion of local farmers and consumers?

How can we spread the awareness and educate more consumers (beyond the urban scale) on innovative farming concepts like vertical farming?

Can a food system actually be fully closed and circular?

Related links:

- Report by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Cities and Circular Economy for Good - Building a food system fit for the 21st century and beyond.

- Small vertical farm kit for home by IKEA.

- Next editions of the Social Tech Tour can be found in our agenda.