The Amsterdam Urban Ecology Pilot of T-Factor explores the Amsterdam Science Park. The goal is to get to know and better understand all living and non-living creatures that use it. This is done by initiating field visits, observing and making notes. This time, the area was explored through street interviews.

“Park, what park?” / “I come here for nature and silence”

“What is your most popular snack?” I ask the father and son, who are the owners and operators of ‘Science Döner’. I just finished drawing out the route of another interviewee on my paper map and I am anxiously trying to find another piece of paper to write on. I struggle, there is a strong wind and it’s radically warm — even for summer time. Luckily, the men of Science Döner are used to fragmented conversations like this. As the faces of the mobile snack truck at this crossroad of the Amsterdam Science Park, they are accustomed to spending only a couple of minutes with their customers, discussing sports and study results, while also taking orders and handing over bills. And of course: preparing food! As it turns out, Turkish pizza is the preferred afternoon snack to turn to.

Why we were there

We just started researching the area of the Amsterdam Science Park, and these first couple of months are focussed on ‘Inquiry and Experimentation.’ Here, the Amsterdam Urban Ecology Pilot of T-Factor initiates a variety of field visits and explorative exercises in order to better understand the values, meanings and usages of the living and non-living entities on site. We’re experimenting with different forms of Participatory Action Research and 'Arts of Noticing' practices. During these practices, we actively place ourselves in, and in relation with, the environment and its participants.

What we did

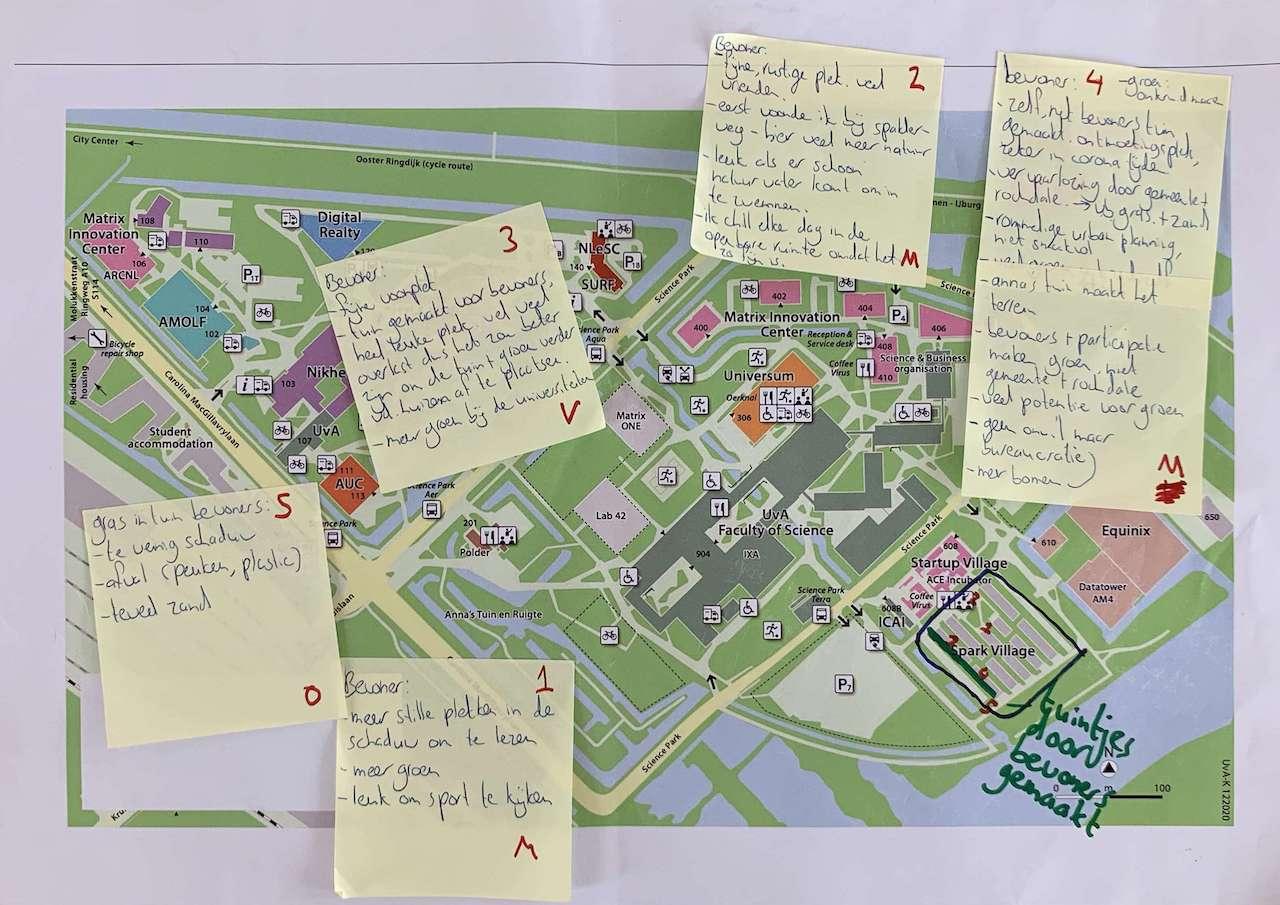

Whilst the first field visit was focused on non-human beings at the Science Park, these two street interview sessions were oriented towards the human interactions with the park. The aim of these sessions is to map the different usages of the area and collect first impressions on the ‘value proposition’ of the park to its users. To what extent is the public space in this park used/underused, what is the human relationship with the urban nature on site? The outcomes of this effort will be flowing back into the development of some exchanges with Science Park stakeholders later this year.

With a paper map in hand and conversation starters in mind, we set out to meet some of the people on site. At the end of the session, we spoke to a total of 24 people, varying from international students and teachers to local kids and newcomers living on site. Most of the interviewees were frequent users of the area, but they were only familiar with some of the areas and initiatives on site.

Insights

Contrary to our assumptions, the appreciation for the use of the park was quite high and it is generally perceived as ‘pretty green’. However, this affection for the site was mainly coupled with a pragmatic use of the area. We spoke to some students who mainly use public transport to reach the park and only visit their university, while neighbours from the surrounding area use the park for recreation and sportive purposes only. None of them really mingle. And the verdict is still out, whether we should consider the Amsterdam Science Park as a ‘built’ or ‘grown’ environment.

The answers of the workers, students and dog walkers align with the impressions and comments that were made by stakeholders in an earlier stage of our research. The representatives of the institution of the park all perceive the Amsterdam Science Park as 'having great potential'—with the site being a vibrant hub of knowledge, education and innovation—but that it was hard to 'find each other'.

Moving more outwardly we noticed that the construct of 'what’ the Science Park ‘is’ and especially ‘where’ it is located became more fluid. With participants confusing the 'park' for the Flevopark, or mentioning them to be one and the same.

It became apparent that, out of all the ‘smaller’ meanwhile initiatives on site, the permaculture garden called ‘Anna’s Tuin & Ruigte’ was most well known as a green space to walk through or reside in. We even met one sustainably-oriented resident who went through great lengths to bring the food waste from her student flat to their compost bin. This stands in stark contrast with the not-as-prominent reputation of the community garden from the inhabitants of Spark Village, who also take pride in the development of their garden, but are more hidden away from sight (“Startup Village is far”!). Plus, they receive much less financial support for the maintenance and improvement of their dried out grasses.

Some surprising comments on the area were made by two female visitors, who were both warned by their friends not to visit the park and the neighbouring Flevopark at night. However, both felt safe when traversing there. This led us to question where these narratives came from, putting the issue of safety and public space on our agenda as one to delve into.

We left feeling charmed by all the personal interactions. It was wholesome to be able to spend time with people in the real world—instead of over zoom.

Curious?

We highly recommend you to also read fieldnote #1 on the non-human niches and visit the park yourself and perceive it with your own eyes. Or - with the eyes of the 'other'.

Want to know more about our projects?