Across Europe, preserving crafts people's knowledge and livelihoods are under pressure. What can we do to preserve craftspeople and their knowledge for future generations? Within the research pilot 'Hacking the Machines', artist and designer Marloeke van der Vlugt and Cecilia Raspanti, lab lead of the TextileLab, are looking for 'craftspeople 2.0' on behalf of Waag Futurelab.

What is a craftsperson 2.0?

Cecilia: Someone who is fearless in combining traditional crafts and modern technology, understands and embraces both, sees both benefits and knows how to harness them.

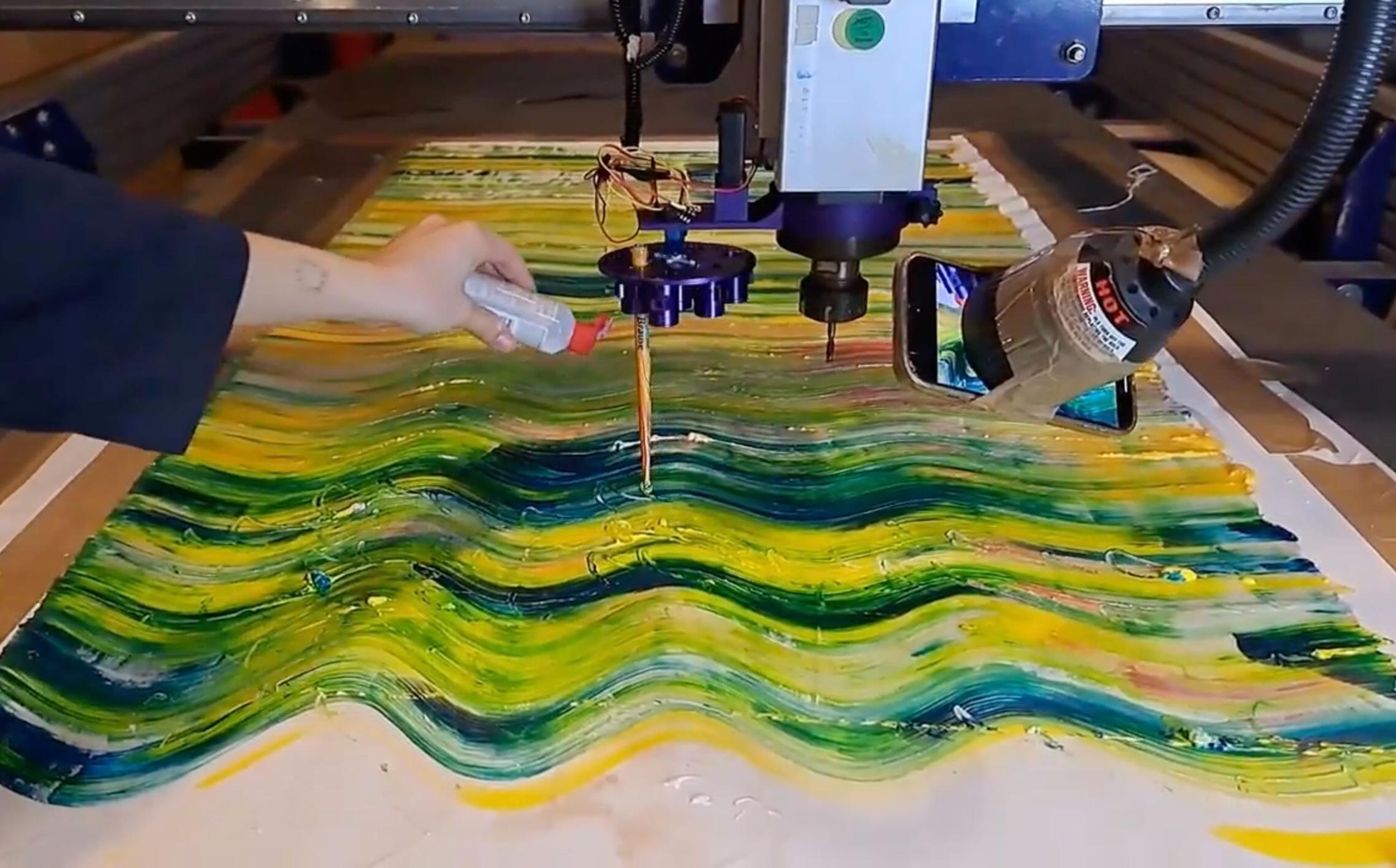

In the research pilot 'Hacking the Machines', Waag's research team is developing an open-source hacking protocol at the TextileLab in Amsterdam. With that protocol, you can convert a computer-controlled CNC machine into an interactive haptic textile printing device, which craftspeople use to print and stain traditional inks onto textiles. By combining centuries-old textile traditions with modern technology, the researchers aim to enable sensory and intuitive creative interaction between the craftsperson and the digitally controlled machine.

An interactive haptic textile printing device?

Marloeke: The typical perception of using a machine is entering a design, pressing the button and sit back. There's no sense of craftsmanship in that; it's mechanical. Within the pilot, we want to explore how to reconnect the machine user with the craft process.

Cecilia: We hope that craftspeople, whether traditionally or technologically skilled, feel connected to the process. Craftsmanship is not only about perfection but also about understanding the interaction between materials and hands. Our aim is not to teach craftsmanship, but to provide technological alternatives that allow you to combine traditional techniques with modern technological applications.

In contemporary craft processes, more and more actions are taken over by machines. When is something still a craft, and when not?

Cecilia: As long as you as a crafts person still interact with the craft process. One of the most crucial insights into what constitutes craft was when I worked with a craft woodworker who reluctantly used a machine to work wood. He said the machine could never deliver the same results as he did with his hands, for the kind of pliable wood he used. I think that is truly an example of craftsmanship. He operated the machine with such a high level of knowledge that the machine deprived him of certain nuances in the process.

When discussing crafts and craftsmanship, do you exclude certain practical professions?

Cecilia: When we met with the research project consortium in Florence, we had an interesting discussion about the definition of craftsmanship with the Swiss and Belgian research partners. In it, you could see that we all thought differently about the essence of craftsmanship. For Belgium, repairing something was a demonstration of craftsmanship above everything else, for Switzerland it was making and creating, and for us, it was more the interaction with materials. The interesting thing was that in this way we challenged each other to create a sharper definition of craftsmanship.

When you make cognac, the vessel it sits in matters, and the type of wood and the craftsmanship of the vessel itself. All the steps you take in a craft process involve knowledge. From your awareness of the materials to the tools you use, all those components are part of craftsmanship.

What are the frameworks of craftsmanship at this point in the research?

Marloeke: The frameworks of craft and craftsmanship are tricky. If you let a machine do the 6,000 hours required to do a craft, is it still a craft?

Cecilia: I think we are shifting the interpretation of the 6,000 hours we put into developing tools these days, optimising a craft process. But when you move from craftsmanship to industrialisation, the priorities tend to become faster and cheaper. Artistic and creative fulfilment then comes last. For a craftsperson, that is the most important element.

Marloeke: A craftsperson knows which part of the process can be done by a machine and which elements they have to do themselves for the best result. It also concerns the craftsperson's intrinsic motivation to improve the crafting process continuously. I find optimise more fitting for economic considerations to improve your process. I would rather call it 'individualising steps in the process'. When I'm processing my fabrics, there are certain steps that I prefer not to do by hand or that I prefer to do by hand. Then I look for opportunities to automate the steps I don't want to do myself.

Cecilia: In the pilot 'Hacking the Machines', we will look for a completely modular process that everyone can apply in the same way. So the process is not individual, but we create a protocol with a framework where there can be room for individualising the steps.

'Hacking the Machines' is part of the European research project Tracks4Crafts. Within this project, Waag is also setting up the online platform 'Living Archives'. An ongoing exhibition of creations emerging from Tracks4Crafts for a wider local and international audience, and at the same time an online repository for the physical, tactile and performative research results and development processes, the machine hacks, the hacked device, series of prints, videos and photos of the 'enriched' craft process.

Cecilia: "The research we do within Tracks4Crafts consists of physical activities and documentation. The 'Living archives' documentation includes everything we do over the next 18 months: from interviews to videos to open-source protocols for replicating processes. The physical results are the 'machine hacks', where we modify (hack) machines for various purposes. These can be both physical modifications and modifications in the software code that controls the machines."

Do you want to stay updated?

Sign up for the newsletter ‘Maker education, digital and cultural heritage’ or follow us on Mastodon or LinkedIn.