For the intangible heritage of traditional crafts to continue, this practice and knowledge of the craft must be passed on. Whenever this practice disappears the immaterial heritage disappears with it, even though the material outcomes of the craft might remain. Digitalisation and open-source networks can be crucial in the continuation of the intangible heritage of traditional crafts. However, some craftspeople are hesitant to participate in the digitalisation of knowledge and look to safeguard the traditional techniques out of the fear that techniques might be misrepresented or they, as craftspeople, might be discredited.

Within traditional crafts there is an importance of sharing knowledge for the immaterial heritage of these crafts to survive. Rather than something physical, intangible heritage is related to traditions, rituals, and practices. How was knowledge about traditional crafts safeguarded in the time of the guilds? And what can we learn from Staphorster dotwork and the value of documenting recipes?

Safeguarded Guilds in Amsterdam

The safeguarding of knowledge and crafts isn’t just something happening at the present time. Guilds were organizational structures of professional craftsmen that protected and ensured the quality of their profession and product. They were linked to a city and possessed a great deal of political and economic influence due to their position. In the Middle Ages, Amsterdam was known for their textile production; in the 15th century, a weaver’s guild and a ‘lakenbereiders’ guild (a draper’s guild) was established in the city, as well as a fabric dyeing guild in the 17th century.

In 1662 Rembrandt famously painted the ‘staalmeesters’ (sampling officials) of the draper’s guild; these ‘staalmeesters’ judged different pieces of fabric on their quality. While most information on these textile guilds have been lost in the archives, the street names of Amsterdam still remind us of that history. For example, the ‘raamgracht’ refers to the cloth weavers situated alongside the canal that dried and stretched ‘laken’ (woven woolen fabric that was felted) on wooden frames. In the Waag building several guilds were housed. They worked within different spaces in the building; each guild had their own entrance leading to their own guild space.

In 1662 Rembrandt famously painted the ‘staalmeesters’ (sampling officials) of the draper’s guild; these ‘staalmeesters’ judged different pieces of fabric on their quality. While most information on these textile guilds have been lost in the archives, the street names of Amsterdam still remind us of that history. For example, the ‘raamgracht’ refers to the cloth weavers situated alongside the canal that dried and stretched ‘laken’ (woven woolen fabric that was felted) on wooden frames. In the Waag building several guilds were housed. They worked within different spaces in the building; each guild had their own entrance leading to their own guild space.

In the 17th century the guild system was weakened in the Netherlands. The introduction of chintz, a colorful cotton printed fabric, threatened several textile guilds and they began to protest the import of the fabric, as well as the wearing of it, in vain. At the end of the 18th century the municipalities of Amsterdam abolished the guild system, which meant that one would no longer have to be part of a guild to practice a profession.

The importance of sharing crafts

The sharing and documenting of knowledge on traditional crafts becomes important when trying to keep intangible heritage alive. In 2017 Staphorster dotwork was granted intangible heritage status in the Netherlands. Women used this craft at the beginning of the 20th century to sell handmade products and bring more money in for the household. The knowledge around this traditional craft seemed to be safe guarded at that time. The recipe for the Staphorster dotwork paint wasn’t recorded and changed throughout the years, either because people were tightlipped, materials to make the paint with ran out, or because the paint was made intuitively.

Currently, this causes a problem for those who want to keep the intangible heritage alive as the paint that has been made for Staphorster dotwork is slowly running out and there is no recipe to remake it. Here we see the importance of documenting and sharing the processes involved in this intangible heritage.

The digitalisation of an intangible heritage can also bring communities together and ensure its existence. For example, knowledge behind Tatreez, a Palestinian embroidery, is being digitalized and recorded through initiatives like Tirazain. For the Palestinian community these archives of knowledge create an essential means and proof of existence.

Tracks4Crafts and open-source knowledge

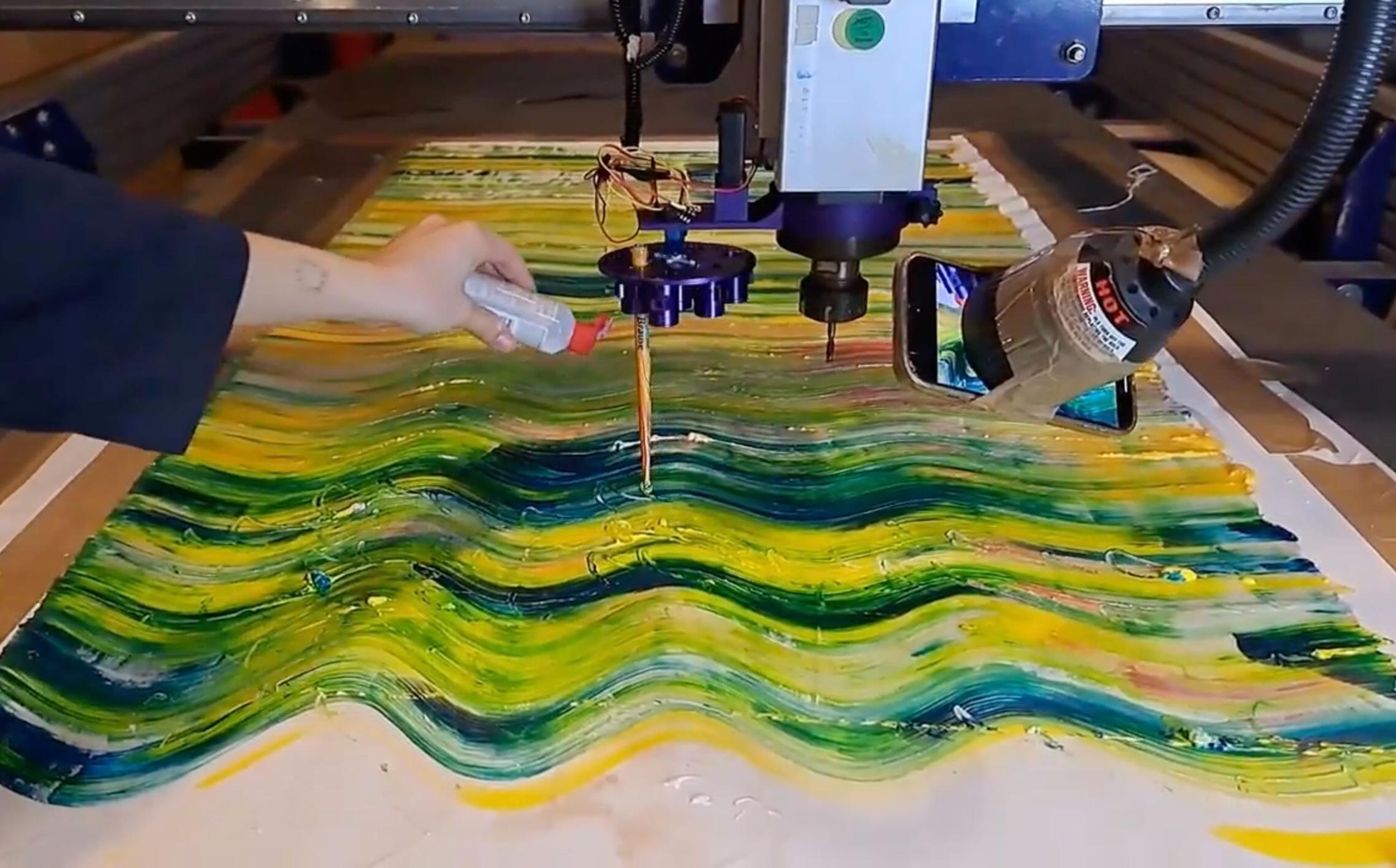

Within the pilot ‘Hacking the Machine’ of the European Horizon Tracks4Crafts project, we strive to create an open-source living archive. Within this archive we share the acquired knowledge and steps in the creation and development of our pilot. By sharing this knowledge craftspeople who are interested can implement, utilize, and build on this knowledge in their own ways. Meanwhile we try to answer the question; how to share knowledge in a way without diminishing the agency of craftspeople and maintain traditional crafts knowledge? Through creating this open-source living archive we can safe-guard traditional crafts knowledge and ensure the intangible heritage of traditional crafts will live on in our future technological society.

Special thanks to Museum Staphorst, and Annekie and Greetje from Stichting Staphorster Stipwerk for sharing their stories with us.

References

- “366 Archief van de Gilden en het Brouwerscollege,” 366 Archief van de Gilden en het Brouwerscollege, May 27, 2024

- Dirk Kok, Kleurrijk Gedrukt. Oorsprong en Ontwikkeling van het Staphorster Stipwerk. (LK Mediasupport, 2014).

- “Tirazain,” Tirazain, geopened op Mei 27, 2024, https://tirazain.com.

- M.S.C. bakker et al., Geschiedenis van de Techniek in Nederland. De Wording van Een Moderne Samenleving 1800-1890. Deel III (Zutphen: Walburg Pers, 1993).

- “Raamgracht,” Joodsamsterdam, Joodse sporen in Amsterdam en omgeving, January 30, 2021, https://www.joodsamsterdam.nl/raamgracht/#:~:text=De%20pittoreske%20Raa…–%20vandaar%20de%20naam%20Raamgracht.