Suzanne van Lier & Joke de Hoogh, teachers at the elementary school de Regenboog in Amsterdam, told us about the experience with Smart Kids Lab in her lessons. Smart Kids Lab is part of Making Sense, a European project that stimulates citizens to measure the quality of their environment.

We started our first experiments in the Smart Kids Lab at school. The Smart Kids Lab is part of a European project concerning the involvement of citizens in their communities. The project has various different components for citizens in Europe, but one of these components was designed specifically for children of primary school age. In Amsterdam, there are three schools participating in the project: the Boven het IJ Montessori school, the St. Jan Montessori school, and Rainbow Montessori school. Through the project, elementary school children will learn how to measure their living environments using specialized instruments and tools they build themselves. The measurements we do together are then shared with others on a dedicated website. This website will allow us to see the data we've collected as well as the data that other project participants have collected. If you're interested in our findings, we encourage you to visit the website: smartkidslab.nl. There, you'll find a lot more information about the project.

But what have we done so far? We started with a baseline: how are the children currently doing in their environment? Is there something they're worried about? Do they notice the quality of their environment? At the end of the project, after measuring various factors in their environment, the children will see how they can contribute to improving where they spend most of their time.

Then the real work started. First, we talked about the PH levels of ordinary things in and around the home. Lemons, for instance, are acidic—we all know that. But is sweet apple juice acidic as well? The school dentist certainly mentioned that it was. Could the ground also be acidic? And, if so, what does that mean for the plants that grow in acidic soil? Hydrangeas like acidic soil, while other plants find it less enjoyable. Soil that is too acidic makes for acidic groundwater, and that groundwater is then used for the production of drinking water. To answer these questions, we began experimenting.

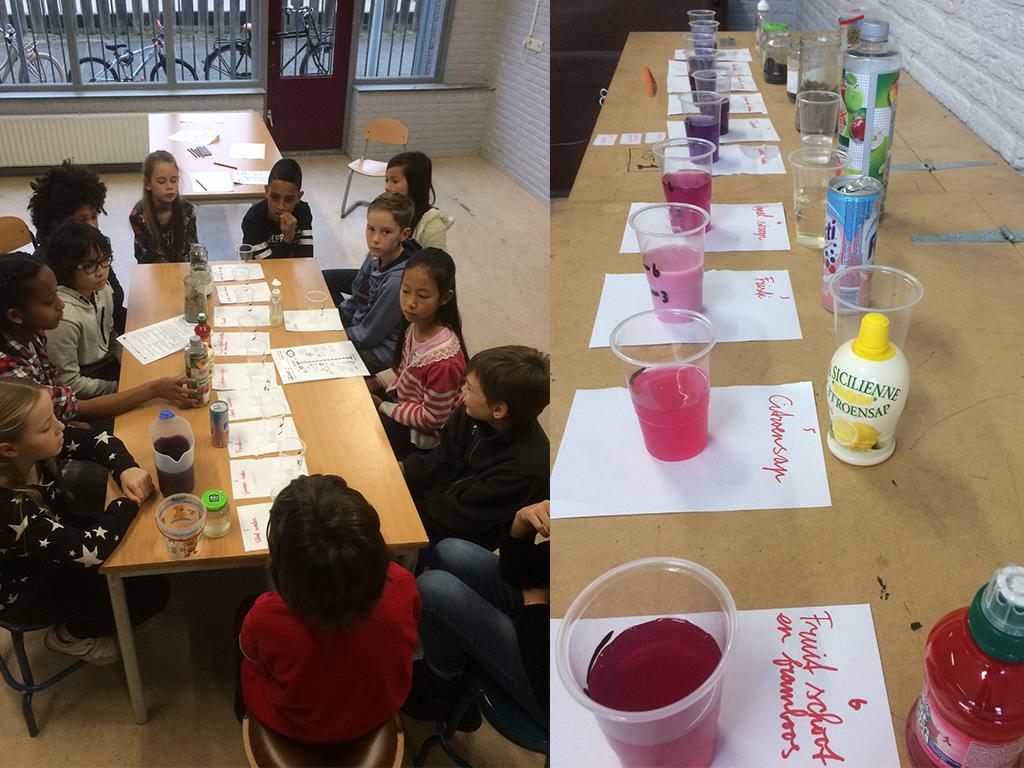

Half of the group went with Mrs. Joke (who joined us for this project) and got to work making our measuring instrument: red cabbage juice. To make the juice, the group mixed red cabbage with water, mashed it with a hand blender, filtered it through a coffee filter, and poured it into cups. The red cabbage juice will change colour from purple to pink and red in the presence of acidic substances. Basic substances (the opposite of acidic, like soap), on the other hand, will cause the colour to change from purple to blue, green, or yellow.

The other half of our group focused on the substances we would be measuring. We had already gathered tap water, lemon juice, Fristi (a fruity yogurt drink), apple syrup without added sugar, and Fruitshoot (a sweet fruity drink). Outside, we collected sand, soil, and ditch water. We also collected two different types of soil: dirt from the garden (where lots of plants grow) and dirt from next to the road. Then we developed our hypotheses. Which would be more acidic and which would be more basic? Ditch water has all kinds of animals and bacteria that produce waste, which might make the water more acidic. Plants don't like soil that is too acidic, so places where lots of plants grow will not be very acidic. Fruit Shoot is very sweet, so it's probably not as acidic as Fristi. And lemon juice, of course, will be the most acidic.

Time to see how our hypotheses played out. We poured purple cabbage juice into cups and then added different liquids. It was very exciting to see the colours keep changing. Sometimes to red, sometimes to a light pink or darker pink. Other times to a deep purple and—when we added the soap—to a bright blue! Sadly, none of our substances produced the yellow colour that accompanies really basic substances. I guess we'll just have to keep experimenting at home!

During our snack, we answered the questions: what did you accomplish after a lot of practice and what are you proud of? It was nice to hear about what we've mastered and how hard we worked for it. You could tell everyone was really happy to talk about how their efforts paid off.

After briefly playing outside, we quickly got to work on making the the fine particulates meter. What are fine particulates and where do you find them? Is there more fine particulate matter on the side of your house facing the garden or the side facing the street? And which window, as a result, would be better for you to open up on a hot day? Where is the healthiest place to go cycling? Along the highway to laugh at the people stuck in traffic? Or on a bike path through the meadows?

Making the fine particulates meter was actually very easy. You can use an empty milk carton to make a meter in no time. Just cut the milk carton into little rectangles about the size of a playing card. Then, coat the white side with Vaseline and hang the card in a place where you want to measure how many or few fine particles are in the air. This test does, however, require some time. We agreed that we would hang the meters in our yards until after the Christmas break. Then we would see how much fine dust is in our homes and surroundings. We also decided that, on New Year's Eve, we would hang a meter in a place where fireworks were set off. How much particulate matter would the fireworks release?