Imagine a city where sidewalks, roads and bicycle lanes are all on the same level. No steps, no stairs: all levels flow into each other smoothly by ramps. You are surrounded by high towers, however, they do not reflect sunlight. Tall facades that were once made of glass are now covered in QR-codes. The newest buildings even have QR-codes integrated in the textures of their walls.

A little grey person rolls by. It does not have legs but moves on wheels, just like a Segway. It is as tall as a 12 year-old kid, but it’s wearing the clothes of a worker. It has a package to deliver in the building in front of you. You look at it. ‘Is it a she or a he?’ you think to yourself. The person smoothly slides into the building via a ramp. Meanwhile, it catches your gaze. It waves at you, and you smile back.

These small humanoid machines are everywhere. Are you glad they are there? How do you feel when they smile at you?

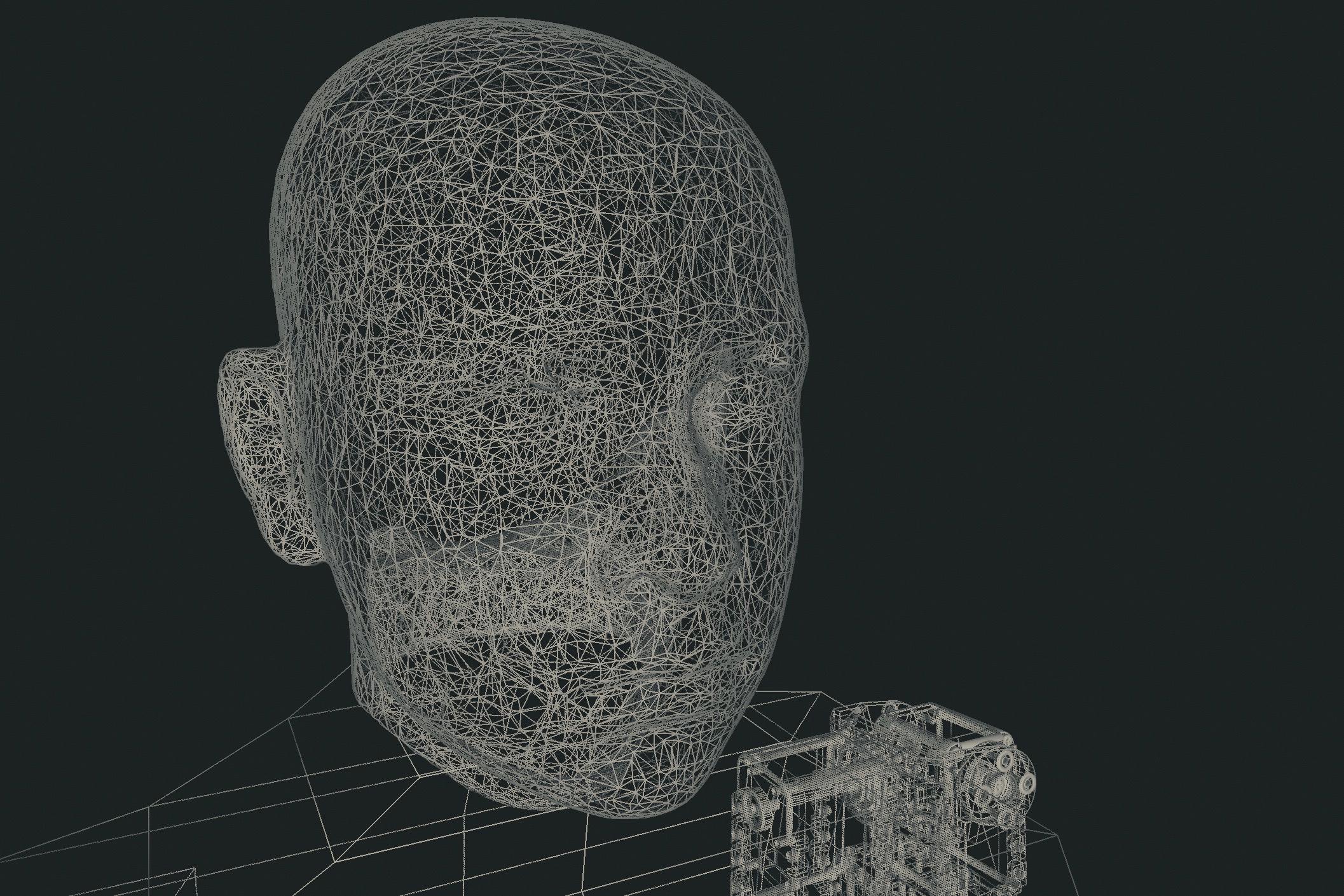

Artists Anna Dumitriu and Alex May developed the robot that was described above for their artwork ‘Cyberspecies Proximity’ during a S+T+ARTS Residency in collaboration with Schindler and Waag. Dumitriu and May question the role of robots in a way that is understandable, by dressing the robot with clothes and manipulating it’s empathetic behaviour. Like humans, the robot reacts to body language. With it, Dumitriu and May experiment with the space that robots can, will or should inhabit. Through emotion computing, they raise awareness on the challenge of integrating robots into society, partially because humans are easily fooled by emotions. Dumitriu talks about the tricks they incorporated into the robot: ‘making the robot smaller makes you feel protected. Putting it in workers’ clothes makes it relatable. And to avoid racial bias we decided on a grey skin color.’ All these seemingly small but conscious choices have large implications when introduced into society on a mass scale. It reminds us of the way we have become culturally wired to believe, think and feel things about a person based on a first impression, when you meet them on the sidewalk.

Since the emergence of science fiction, robots have been presented as human figures. A Frankenstein-like obsession of ‘creating life’ was introduced in film as soon as it was technically possible. From Maria’s robotdouble in Metropolis and Robbie the Robot to Ex Machina’s Ava.

Today, the image of a human robot is not fictional or futurist anymore; it has become real and tacit. Making robots look and behave like humans and placing them into ‘real’ public life presents us with many new issues within the already heated debate of social inclusion, labor rights and sharing space. Now, robot ethics are starting to materialise in a way that is parallel to human ethics.

The artistic experiments of ‘Cyberspecies Proximities' show us how the looks and behaviours of robots determine their role and position in society. Along the spectrum of robotic design, we see many types emerging next to humanoid robots. If you’d want, you could already purchase robots shaped like animals, insects or plants. For example: Maah is an emotional and social robot using body language. It looks and moves like a bug and has a textile fur, it is a ‘living’ furniture piece that gives companionship. An animaloid robot instinctively raises less questions about inclusivity, as it imitates a relationship of humans and pets. A plant-like robot with the characteristics of a living organism generates even lower expectations of communicative and emotional skills. Perhaps they would be easier to include into our circle, just like plants in the living room and trees on the sidewalk.

Are you glad they are there? How do you feel when they smile at you?

Some robots aren’t as obviously linked to species, if at all. Think of entire robotised warehouses, industries or homes. Dumitriu and May address possible relationships of such robotic systems with humans. The same little grey robot now appears on the walls of Schindler’s elevator, shaped as moving pixels and geared by the same behavioral code as the robot. It is also known as a ‘digital twin’. With it, an entirely new relationship between elevators’ robotic system, humans and buildings open up.

The magnitude of robotic design possibilities seem infinitely large. Especially if we consider the fact that, globally, we are in an endless race for technological development. It underlines the indisputable truth that robots will inhabit the earth. That is why now is the time to ask the right questions about what is or isn’t wanted for robotic design.

Dumitriu and May’s work contributes to this discussion without trying to solve all technical issues. They show us we need to learn about humanoid robots’ social impact, ethical challenges and urban consequences. At the same time, their work feeds into a larger conversation through comparison with any other imaginable or already existing robot.

Many robots aim to provide faster services, more money or companionship and ‘happiness’. But in the light of today’s terrestrial troubles, shouldn’t we start to think about more selfless issues and strive for robots that help us humans to create a more liveable planet?

Probably.

Then the next question would be; what designs enable a profound and harmonious co-existence of robots and all other life on earth? What species inspire these designs? And more importantly, who decides: politics, the market, scientists, engineers, sciencefiction-writers, artists or the public?

The VOJEXT project has received funding from the European Commission under the H2020-DT-ICT-03-2020 call under Grant Agreement number 952197.