Cities are the dominant and most successful organisations of human endeavour. This intense form of cohabitation has developed over thousands of years, attracting an increasingly larger part of the human population. While they have vibrantly developed in terms of size, density and quality of life, technology has sped up, leading to problems and possibilities that we still have to fully apprehend.

To many contemporary government officials, there is no more silver-lined allure than the mantra of the “Smart City”. Smart Cities are essentially networks of sensors strewn across the city, connected to computers managing vast flows of data, optimising urban flows like mobility, waste, crime and money. They promise to make governance more efficient, and turn cities into safer, cleaner and more enjoyable places. This technocratic rhetoric, that stresses efficiency and control over serendipity and dialogue, might well do more harm than good, since it takes humans out of the loop and turns them into passive rather than active agents.

Citizens, on the other hand, have become smarter than ever; appropriating new technology at an incredible pace. In just over a decade, they have embraced mobile phones and social media, repair cafés and maker spaces, crowd funding and crowd sourcing. The power individuals have to influence others, even on a large distance, is unprecedented in history. While citizens became self-directed, funded and employed, governments often still regard them as customers, or even nuisances in the way of progress.

However, the power balance has changed and it is clear that citizens need their governments and governments need the intelligence and the cooperation of their citizens to function well. This demands a change in how cities are governed. Cities need to (re-)design and implement procedures, services and (technological) systems in ways that acknowledge the new role citizens take. No longer should they be designed top-down, and then poured over citizens without them having an active role in their conception, development and delivery.

Experience in participatory platform design suggests that to guide the design process certain principles are needed. City officials should implement them whenever they devise a new policy, rule or project:

- Your citizens know more than you. Don’t coerce or just pretend to listen, but engage in a dialogue about what should be done, and how. Employ violently neutral facilitators that will take power out of the equation.

- Don’t separate the design and development process: they are one. Prototypes will make design issues tangible and understandable to the people that participate. Prototype early and fast, engage the stakeholders, iterate quickly and be prepared to start all over.

- Embrace self-organisation and civic initiative, but help to make the results sustainable and scalable. Bureaucracies can never muster the passion and energy that citizens have to start new ventures, but do play an important role in further implementation and scaling. Where possible, become a launching customer.

- Know what you are talking about in the face of technology. If you procure a platform, product or service, have people that built them in the procurement team in leading positions. Never rely on consultants that will sell you more consultancy, not solutions.

- Have binding decisions made at the lowest level possible and actively preach self-governance. No good system was ever built by committee, and no committee ever improved a decision that was made by the people who have to use it.

- Favour loosely coupled, smaller systems over monoliths and mastodons, and use peer-defined standards to glue together the parts. Small systems tend to fail sometimes; large systems fail for sure. Furthermore it enables small, local companies to do the work: they work twice as hard for half the money.

- To raise and deserve trust, build systems based on data reciprocity and transparency. People want to know as much of the system as the system knows about them. Be open of what it captures and who has access, and let the people be in control of their data.

- Reuse existing parts and design your additions for reuse, adding to the public domain and thereby strengthening its capacity to act and learn. Open content, open source and open data will be beneficial to all and “make all bugs shallow”.

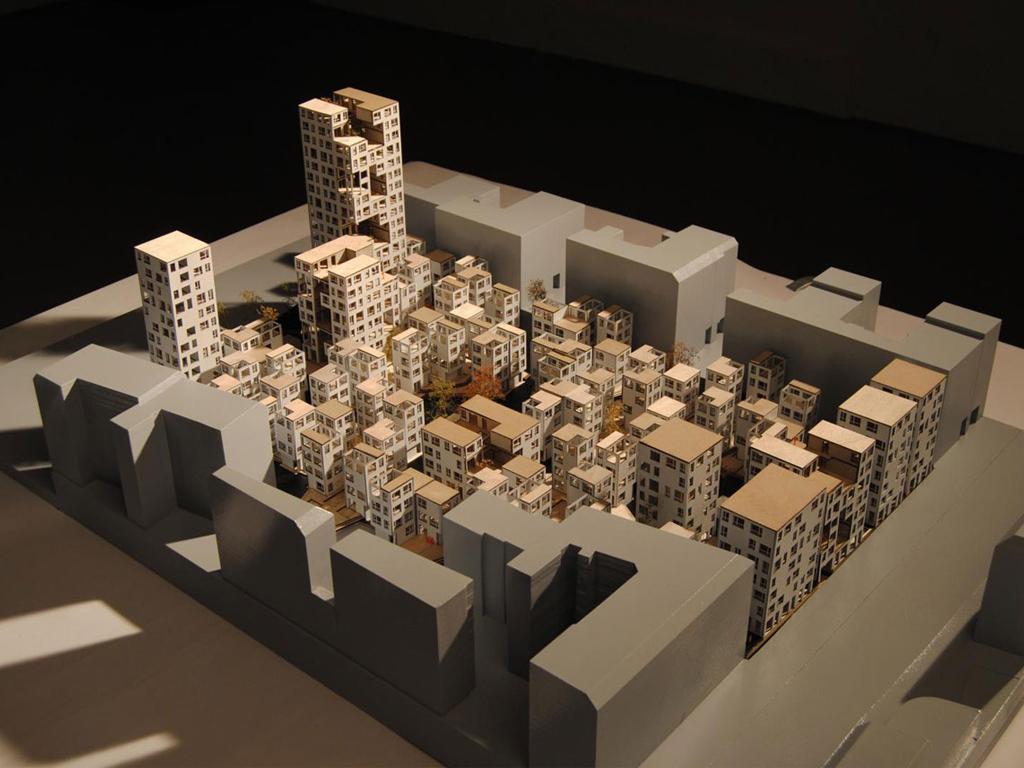

The successful application of some of these design rules to governance can, for example, be seen in participatory budgeting, collaborative urban planning and distributed energy production initiatives. Hard evidence is as yet limited. However, experience indicates that systems, thus designed, will add to the complex city dynamic instead of stifling it. They will help to re-establish agency and trust between the ones who live, work, and raise their children in these cities, and the ones that are assigned to govern and manage them.

Any help on furthering these proposed design rules is highly appreciated – please get in contact. Smart Citizens abound; now it takes Smarter Cities to grasp their potential and build the systems that the 21st Century needs.

(Published in 'Smart Citizens', a publication by FutureEverything.)