How can craftspeople bring traditional crafts and technology together? Within Tracks4Crafts, a Horizon Europe project, this is an important question to be answered. It might seem that innovation and craftwork are two things that don’t mix well together; traditional craftspeople are at times worried that traditional crafts traditions might be forgotten and replaced through this innovation. However, technological advances can also create positive outcomes and innovations in crafts and cultural heritage. What lessons might we learn from innovations in history, and what do they mean for the future?

Were crafts always innovative?

In the early 17th century, an innovation was introduced to Europe that would change the ways of textile production. Chintz, a colorful patterned cotton fabric from India became an obsession in Europe from the mid 17th century till the late 18th century. The fabric was first introduced to the Netherlands by the VOC, who used this fabric to trade for spices in Indonesia. The ability to create lasting colorful patterned fabric wasn’t known in Europe or the Netherlands and soon chintz became a commodity. Chintz started to be used as wallpaper in the houses of wealthy merchants and later was introduced as fashion in upper society. Orders for chintz rapidly increased ; however, it could take three years to get the fabric back from India. This is how the first block-printing workshop in Europe came to be established in Amersfoort in 1678, capitalizing on the growing demand for chintz fabric. Here an Indian technique of printing cotton fabric with wooden blocks was used to create chintz. Soon more block printing workshops were established throughout the Netherlands; in Amsterdam around 80 block printers were situated mostly alongside the Overtoom. The expensive cotton chintz started to become available for cheaper prices, causing the fabric to be in fashion for the commoners and, eventually, left its traces in the traditional clothing of different regions in the Netherlands.

This block printing technique brought about the ability to create prints on fabrics, a technique that wasn’t previously known in Europe, changing the availability of fashion for the lower classes. However, it also further affected the already increasing need for cotton and the creation of plantations which caused millions of Africans to be enslaved and forced to work on these plantations. The rivalry within Europe to compete with Indian textile production created the start of the mechanization of textile production and was a stepping stone for the Industrial Revolution, which caused many craftspeople to lose their jobs to machines.

The struggle for agency next to innovation

Innovation within crafts isn’t new; spinning of wool first started with drop spindles then moved to a spinning wheel. Nowadays you can spin wool with battery-driven spin machines. Mechanizations that were once considered modern can now be considered traditional crafts - block printing is an excellent example of this as it was a way to quicken the hand-painted process of making chintz. The tools used in block printing also inspired the craft of Staphorster dot-work around the year 1930 , and this craft is now considered intangible cultural heritage in the Netherlands. Innovation isn’t something to be afraid of - technology can create, inspire, and help the crafting process. The question should be; how can society ensure that craftspeople aren’t overtaken by the machine and keep their agency?

Mass production caused craftspeople to slowly disappear from the playing field, unable to make a profit in the battle against the machines that were able to make things in the blink of an eye. In the case of chintz, there was no reliable differentiation between the handpainted Indian chintz and, what was considered at the time mechanized European blockprinted chintz in the 18th century. The authenticity of handpainted Indian chintz was lost because of the unclarity surrounding the provenance and the absence of clear labels between the authentic handpainted chintz and the blockprinted chintz.

Preservation of traditional crafts goes hand in hand with sustainable innovation

During the mid 20th century when Staphorster dot-work was being developed, synthetic paints were used in the process; nowadays this is a cause for problems for the Staphorster dot-work community. Synthetic paint creates the characteristics of the traditional dot-worked fabric; it adheres to the fabric without being absorbed, doesn’t crack when dry, is slightly glossy, and creates a perfect drop-shape on the fabric. However, most ingredients used to make this synthetic paint have disappeared from the market creating a shortage of the paint and endangering this new form of intangible cultural heritage. The Staphorster dot-work community is looking for sustainable ways to innovate their paint, trying to create a paint that encompasses the traditional characteristics of the old paint through natural ingredients - this proves to be difficult.

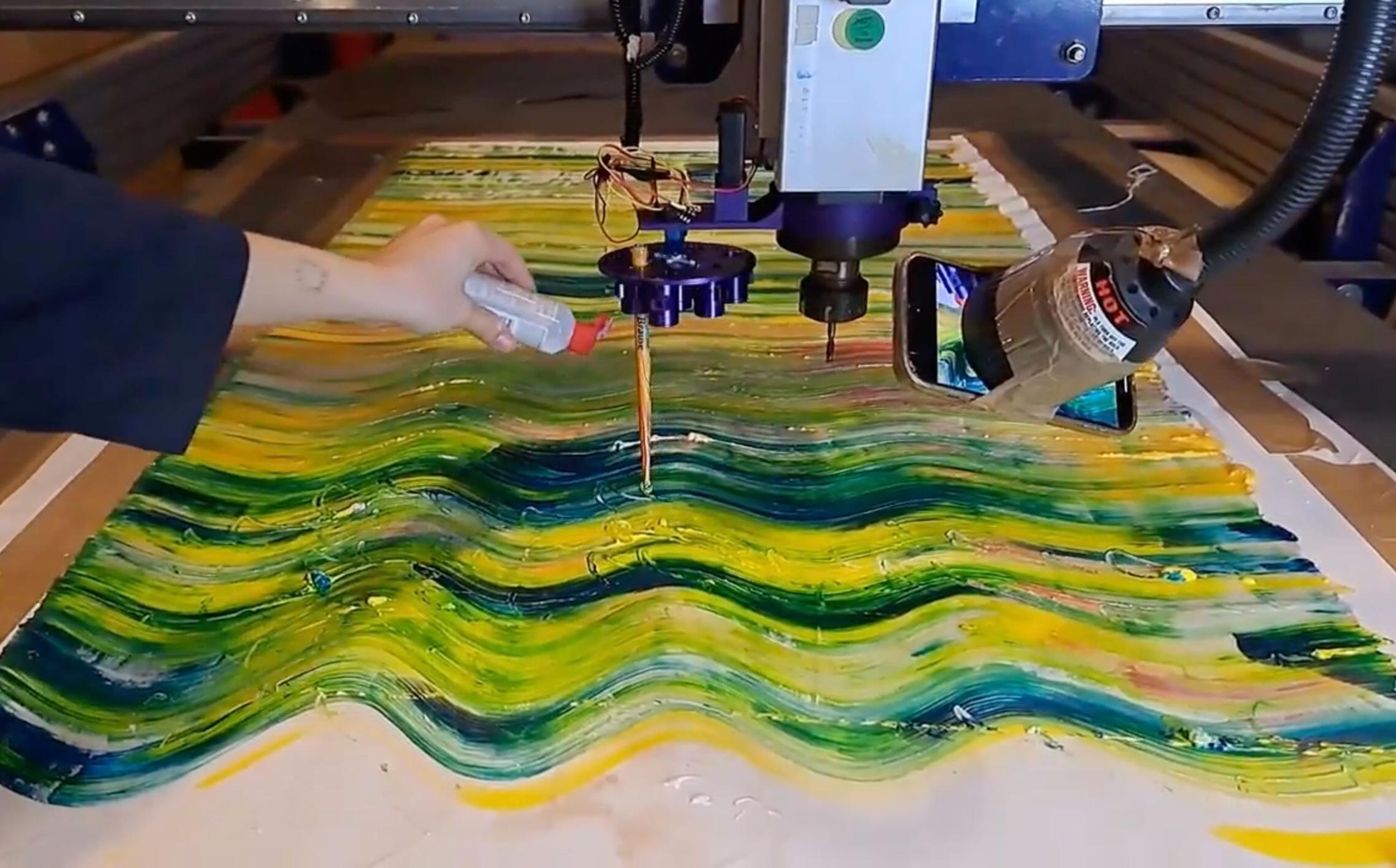

It becomes important to ensure sustainable innovation in terms of its viability as well as its ecological impact. Within the Tracks4Crafts pilot, we work towards creating innovation within the crafts through sustainable environmental ways, looking to create further collaboration between technology and the craftsperson where the agency of the craftsperson stands central. Among other things, we are investigating how natural pigments can be used for textile printing. This research could perhaps further support the Staphorster dotwork community in their pursuit of sustainable innovation.

Big thank you to Nathalie Cassee from De Katoendrukkerij, Museum Staphorst, and Annekie and Greetje from Stichting Staphorster Stipwerk.

More about Tracks4Crafts

Within the European research project Tracks4Crafts, we are looking to personify and define a craftsperson 2.0. A guardian of quality and intangible heritage, who is also able to enrich a craft with modern techniques. At the same time, we explore how to help realise an organic transfer of knowledge between craftspeople of today and tomorrow. Tracks4Crafts is a four-year project with a consortium of 15 partners in 11 countries, funded by the European Commission.

Do you want to stay updated?

Sign up for the newsletter ‘Maker education, digital and cultural heritage’ or follow us on Mastodon or LinkedIn.

Reference list

Dirk Kok, Kleurrijk Gedrukt. Oorsprong en Ontwikkeling van het Staphorster Stipwerk. (LK Mediasupport, 2014)

Ebeltje Hartkamp-Jonxis, When Indian Flowers Bloomed in Europe. Masterworks of Indian Trade Textiles, 1600-1780 in the Tapi Collection (New Dehli, India: Niyogi Books, 2022)

Gieneke Arnolli and Sytske Wille-Engelsma, Sits Exotisch Textiel in Friesland (Zwolle: Uitgeverij Waanders Drukkers, 1990)

Giorgio Riello, “How Chintz Changed the World,” in Cloth That Changed the World, The Art and Fashion od Indian Chintz, ed. Sarah Fee (Yale University Press, 2019)

HALI, “How the Dutch Made Chintz Their Own”

Winnifred de Vos, Pronck & Prael Sits in Holland, Hoe Indiase Sits Het Nederlandse Leven Veranderde (Zwolle: Waanders Uitgevers, 2019)