First and foremost, this isn’t another “China is weird” article.

In 2014, the Chinese government started its pilot of social credit system (SCS). In few words, the SCS allocates or removes points to citizens depending on their behaviour deemed positive or negative. It’s an assessment of financial, social and even political trustworthiness. For instance, jaywalking, expressing criticism towards the government on social media or spending too much time playing video games are considered as misconducts. It’s confirmed by Chinese authorities that the outcomes of this SCS could heavily impact citizens’ life by determining which job they can get, which schools their children can go, whether they’re able to travel etc.

Many were quick to compare the SCS to Black Mirror’s “Noisedive” episode. The series, although remarkable, seems to have wrongly become the main source for the analysis of contemporary phenomena we don’t really want to take the time to understand. This little article is an attempt to move away from the eurocentric views expressed in various media, framing Asian lives as this far-away incomprehensible breed.

Firstly, the SCS is not “Noisedive” for the very simple reason that the score is not determined by the people you meet throughout your life but whether by the government and massive private enterprises, which is probably much worst. So the next time you’ll angrily write “crappy service” on a restaurant review because you had to wait more than 10 minutes for your pad thaï, I hope you’ll realise that you’re the one closest to “Noisedive”.

Chinese citizens in favour of the SCS are obviously not just enjoying governmental surveillance, but they see considerable benefits to it. Those who possess high credit scores receive great discounts on Alibaba marketplace or could have the right to skip housing waiting list. I think we’ve all seen people doing disturbing things just for the chance to win a 3 days trip to Malaga, so no judgement here. Additionally, the SCS is said to be the government’s solution to a trust crisis. In a country where around half of the contracts are not respected, fake and dangerous goods are distributed almost freely and a rampant corruption has become publicly visible, strong distrust has come to characterise the Chinese society.

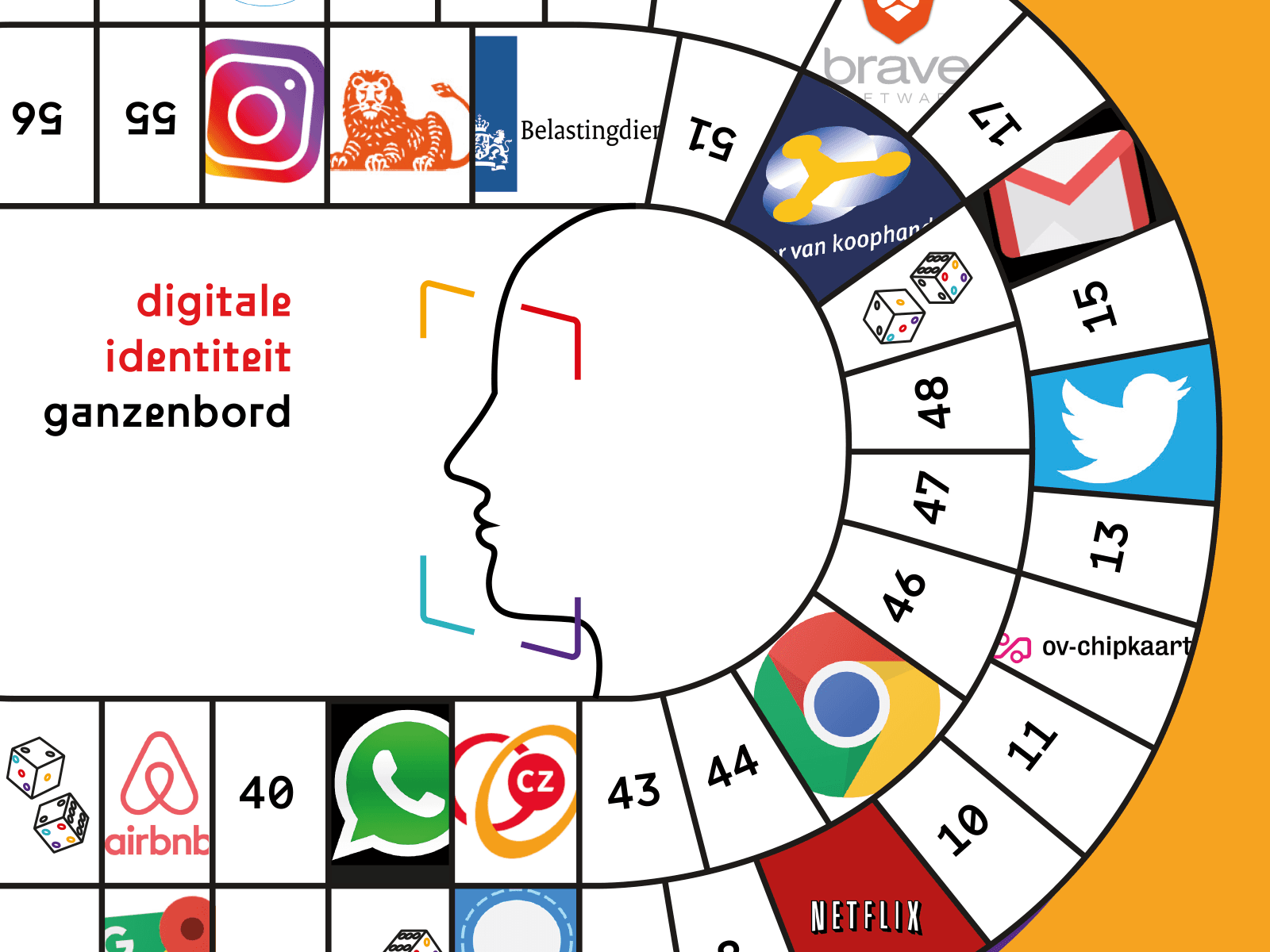

The other narrative I want to debunk is the idea that what is going on in China, is totally inconceivable within our european context. For now, eight private companies, including the giant Alibaba, have the authorisation to perform the SCS pilots before the Chinese government launches its own SCS in 2020. The Chinese government is expected to use the data those eight companies are amassing for its own future system. Well well well, private companies using their users’ data while nurturing good relationships with governments… Sounds familiar right? It should be because it’s currently happening in many instances such as Google transforming an entire neighbourhood of the city of Toronto into a smart city laboratory or the Dutch transit card company Translink giving away users’ data to the government education service. And this trend is set to stay in the upcoming years with the increase in privatisation and the spread of monopolies.

The critics of the SCS seem to forget that our lives are already heavily quantified and rated. We accept paying varying amounts for our insurances and loans based on our age, lifestyle, work, zip code etc. We love rating places and even people while ignoring the possibility of wiping out years of work. It’s not a governmental and centralised scale rating, certainly, but it has become so common that we don’t seem to see it anymore.

The SCS has attracted much attention because it is objectively scary and disturbing on many levels. Of course the SCS, while being presented by the Chinese government as the solution to a national problem, is also a way of reinforcing surveillance and control over citizens. However, we should realise that the particular forces playing in the SCS are slowly taking place in Europe too. Authorities using technology which violates privacy for the sake of public order is a narrative very much present here too. Plus, smart cities nudging people’s behaviour into “good citizens” are already here.

But as opposed to China, we are still enjoying a certain degree of freedom and democracy which gives us leverage to reject this trend. The European Union’ attempts to serve as a watchdog, notably with the GDPR, might not be enough against internet giants. As users, we have to fight for alternatives to these monopolies detaining every bits of our digital (and non-digital) life. Because today, what is at stake is not only about few companies knowing our tastes and interests but also about those entering significant aspects of our lives such as health care and urban planning.