Destruction is at the core of the way our human body is designed. The process starts when we are born and, as no one lives eternally, we are part of an infinite cycle of life and death. When we die our residual mass can be returned to earth. It continues to renew the soil of the planet and gives space to new life.

That’s life, you may think. But that process of life does not seem to be part of modern-day reality. Today we live in brick homes, walk on paved streets and construct with steel. Almost everything we use is made of dead matter. The assumption of the construction industry is that this is the way we should build. Not surprisingly, the first thing architecture students learn are the three principles of good architecture: firmitas (durability), utilitas (utility) and venustatis (beauty). And who is to say a building should not be durable?

After reading this blog you might agree (or strongly disagree!) that building with dead matter can soon be part of outdated traditional architecture - a practice that evolved through a short, revolutionary but destructive history of industrialization. A story of an industry that extracts, exploits, demolishes, burns and gives back nothing. Architects of 2020 know this and with the circular economy taking root, a mindset shift is spreading. Recycling and up-cycling are necessary measures, yet they do not contribute to recovery of soil, air or trees. The construction industry needs a new story in line with nature: a story of life.

During the S+T+ARTS talk, architect and artist Andrea Ling and dr. Brenda Parker, a bio-engineer at London University, presented their work within this new story. Both have entered the young field of researchers that scratched the surface of the potential of engineered living materials. Organisms could give living functions to material building blocks. One of dr. Parkers’ projects uses ceramic tiles lined with algae, a natural micro organism that can help to capture contaminants in water and remove pollution from industrial sites. In Ling’s artistic research at Gingko Bioworks, she dived into the use of geometry to stimulate biological activity. Through computational design, lasercutting and 3D-printing she imitates nature’s complex forms in which bacteria and fungi can grow. Her vision is to implement this structurally, and to change existing structures by using biodegradable matter. In a way, she thus overthrows the first principle of ‘good’ architecture: firmitas. She even calls it: ‘Design by decay’.

Designing with decay means embracing the risks that are outside of our own making and planning.

With that, Parker and Ling design with nature at the core. This means they need to design as nature does: temporal, responsive and through growth. Their works show that building with organisms can take over the way industry builds: standardized, linear and ‘permanent’. What the future needs, is to facilitate nature’s growth. This is challenging. As an architect, Ling knows how the profession requires ultimate control over a design and its materials. Ling: "I had to learn about all the aspects of biology; that some things work in contradiction to what you have planned. Designing with decay means embracing the risks that are outside of our own making and planning."

So how does architecture made of living matter work? Parker and Ling corner a few principles:

• Decomposing and composing matter at the same time

• Access to circular systems

• Ability to grow and adapt

• Produce out of garbage

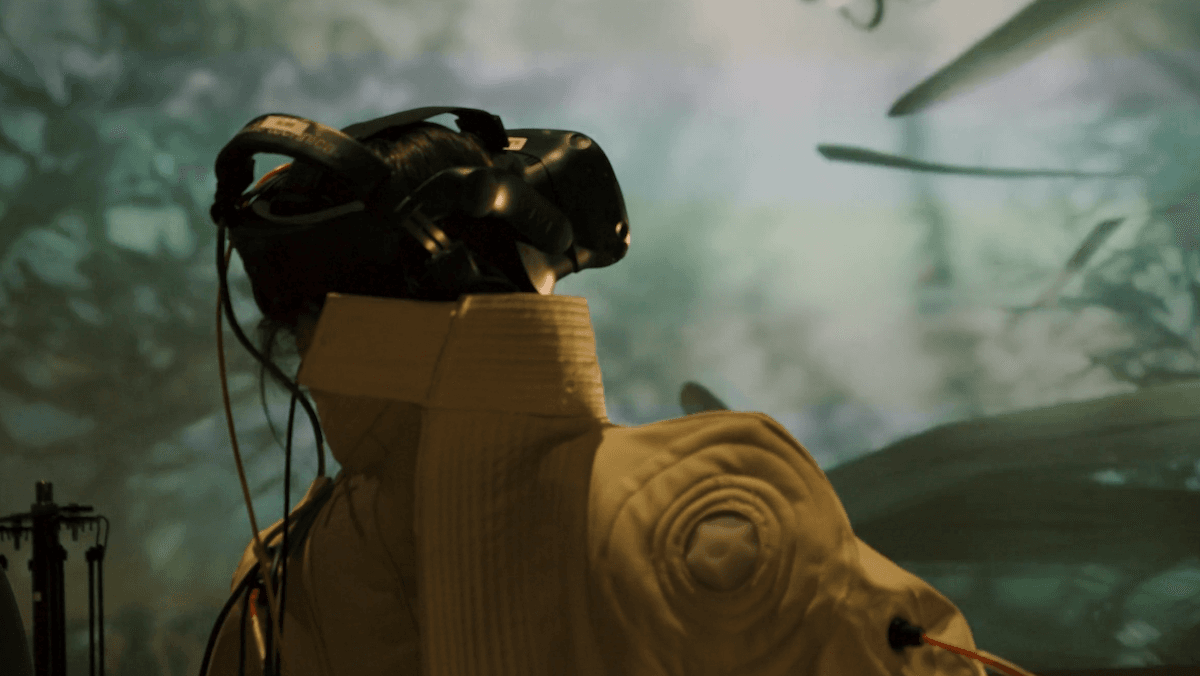

With the Mediated Matter Group at MIT, Ling moves from microscopic experiments to a full scale architectural structure, the Augahoja pavilion. She works with living matter; enzymes, bacteria and fungus. Robotic deposition of organic base materials - cellulose, chitosan, and pectin* - allows for the creation of a generative surface pattern that changes the stiffness and color of panels in response to weather variables. At the end of the pavilions life it will degrade in water to give new life. The result is a system with unseen efficiency. In essence, ecology becomes a technology.

It reminds of the ecological burial method visualized in the painting ‘The Garden of The Happy Dead’ by Hundertwasser. This architect and painter imagined trees growing out of people. In this way the human body has not died, but lives on in the tree. This is a controversial idea, which shines light on how we humans seem to have a hard time acknowledging the concept of growth through death.

Coming back to architecture, the future of construction points towards decay as a natural outcome of a building’s life cycle. Architects, in turn, will need to overcome the illusion of creating permanence through landmarks, white cubes and anti-gravitational masterpieces. Such a shift is especially hard in a discipline that works slowly and where innovation rarely makes it to the construction site.

It is the designers role to know how nature works, and to learn to work with the inevitable.

Fortunately, architects have already begun to open up towards the aesthetics that come with forms and processes in which life occurs. Think of permeable surfaces, multiple layerings and infinite curvatures. In 2011 architect Lars Spuybroek expressed his longing for “the day when I can see objects forming, like pools of mud, flowers on a wall or clouds in the sky.” His design for the Son-O-House, resembling a giant leaf fallen to the ground, already hints towards the aesthetics of Aguahoja.

Synthetic biology and engineered living materials will play a critical role in the face of climate change, disaster and overburdened infrastructure. For this, not only architects but also scientists will need to let go of control. Ling sees how scientists can work for years on an attempt to control organisms into doing something it does not want to do. Lings advice: “If it does not want to grow, don’t force it. Find a new way. The organisms will not listen to any demand. It is the designers role to know how nature works, and to learn to work with the inevitable.”

* Chitosan = made from base material chitine which is found in the cell walls of fungi and the exoskeleton of insects and crustaceans such as lobsters.

Cellulose = plant residue

Apple pectin = the adhesive of the skin of fruit

> Check out the work of Esmee Geerken, Waag's artist-in-residence also working with natural materials for building.