By: Maarten Smith

Curious about the BioHack Academy? Visit the Academy Show 2022 on May the 12th!

In the BioHack Academy participants from various backgrounds learn the basics of biotechnology, work with biomaterials and collaborate on building their own lab equipment. As a researcher sharing in the responsibility for running the academy, I find myself wrestling with a variety of questions, among which the question of what a lab is.

This is an important question, as its answers have consequences for what makes sense to do in a lab, and what doesn’t. I invite you to join me in reflecting on the way the participants of the BioHack Academy approach this question in practice and to see what we can learn from them.

A strange tribe of compulsive and manic writers

We are in good company. There have been many attempts to describe what a lab is. A famous example is ‘Laboratory Life’ by Bruno Latour and Steve Woolgar (1979) in which the authors describe the lab as a place where material substances are transformed into inscriptions. A ‘strange tribe’ of ‘compulsive and manic writers […] who spend the greatest part of their day coding, marking, altering, correcting, reading, and writing’ (p. 48-49). Lab machines are ‘inscription device[s]’ that have the sole purpose of ‘transform[ing] a material substance into a figure or diagram" (p. 51).

Another example is the work of Don Ihde (1979). While Latour foregrounds linguistic or textual aspects of the lab, Ihde emphasises the embodied way in which technologies in the lab ‘mediate’ the experience of the world of those who engage with them.

To see how the question is approached by the participants, let’s take a look at several examples of everyday activity in the academy. To begin, I observe them as they are introduced to a laboratory-grade microscope. Most of them for the first time, others have worked with one before.

Errors or opportunities

We’re looking at foliose lichen from up-close. One of the participants reaches for the controls, gingerly turns the coarse focus knob and then stops. ‘How do you get good pictures? Is there a way to hook up a better camera?’ she asks. ‘I have a really good film camera, it would be a shame not to use it’[fig. 1,2].

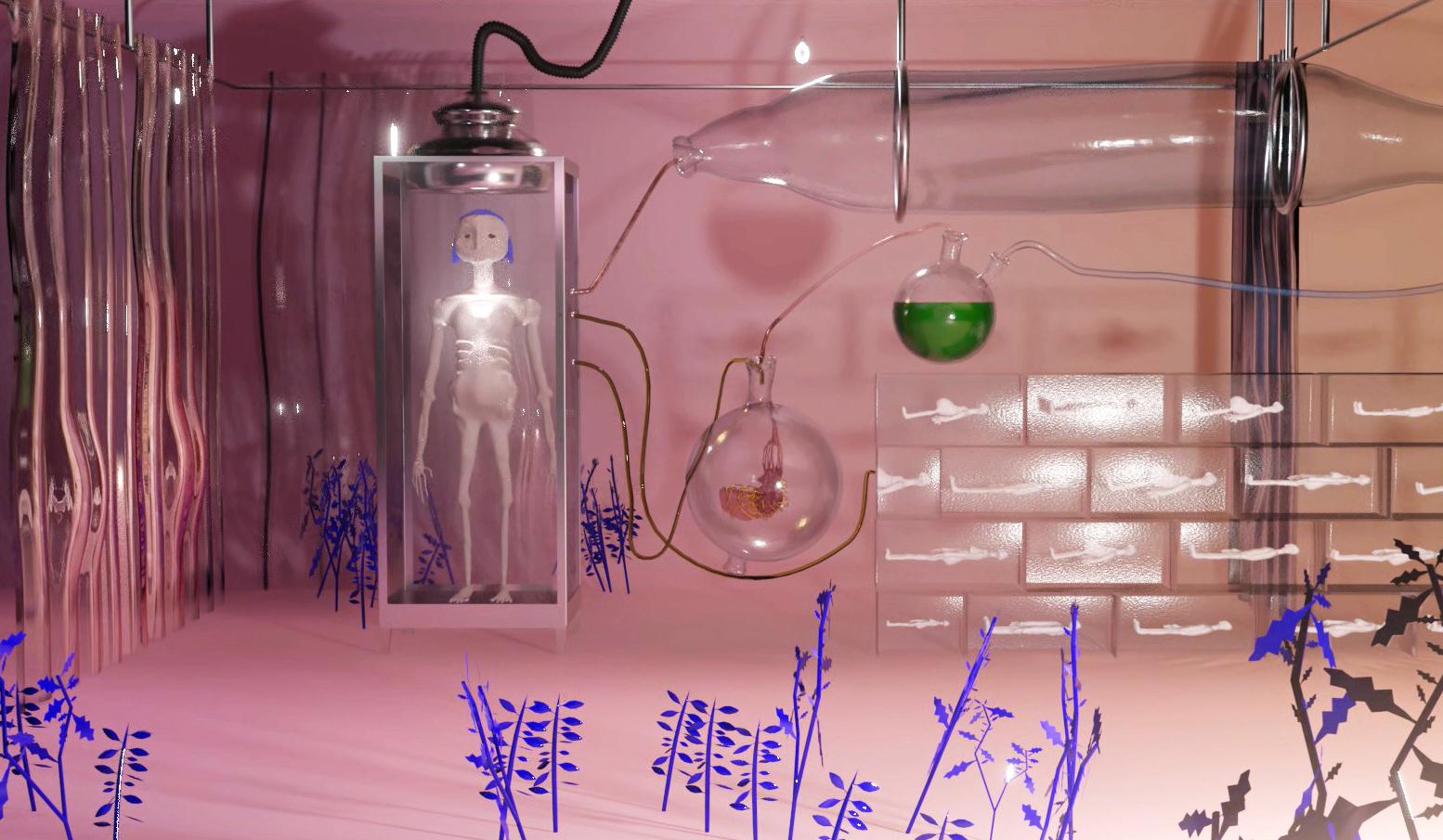

In another instance, the participants spend the day building DIY lab machines [fig. 3]. One of the participants wonders whether he can build a flow cabinet that simultaneously functions as a fume hood. This would allow him to blow sterile air over his desk while he’s doing biochemical work and suck up the fumes from his soldering iron when he’s working on electronics.

On another day, I join the participants in putting together a growth medium for a protocol. To solidify the medium they add agar-agar, which works in a similar way to gelatin. One of them takes a bottle out of the microwave to see if the agar-agar in it has dissolved already. It hasn’t. ‘Wait! Don’t put it back yet! Someone calls out. We watch the half-dissolved agar gel as it forms slow-moving bubbles [fig. 4].

‘Shine a light through it, maybe it will reflect on the ceiling!’ These bubbles would be considered an error in a typical biomedical lab, but here, they are approached as an opportunity that might open up a new direction in the making process.

Alternative ways of laboratory work

These examples illustrate that the BioHack Academy students, whether they are artists or designers, approach understanding the lab in a refreshing way. Rather than searching for an answer to the question of what a lab is, they investigate what a lab could be. They explore what the outcomes of lab work could be, as in the case of the lichen under the microscope.

The participants think of what the instruments and tools of the lab could be and reinvent them to suit different purposes and requirements. Further, they investigate what protocols could be and interrupt them when they see new possibilities for action, as exemplified by the agar-agar bubbles. The outcomes, equipment and the processes become raw material for making.

At the same time, the making process, as it unfolds, structures what the participants find relevant to pay attention to in the lab. By investigating what a lab could be, the participants treat the lab as something unfinished. Furthermore, they are aware that laboratory practices have the potential to change. This way of understanding makes room for a plurality of descriptions of laboratories and redirects its focus from a search for stable definitions to a future-oriented inquiry into alternative ways of practicing laboratory work.

References

Latour, B., Woolgar, S. (1979). Laboratory life: The [social] construction of scientific facts. Princeton University Press.

Ihde, D. (1979). Technics and praxis: A philosophy of technology. Boston Series in the Philosophy of Science. Dordrecht: Reidel Press.

Continue to biohack and playfully research

Subscribe to our monthly Make newsletter! (Choose: Digital fabrication, biotech and new materials, artistic research). And stay updated on our latest blogs, events, open calls and workshops.

Or join the Academy Show 2022 on Thursday May 12th from 16:00 hrs. until 20:00 hrs.