History

Don’t take the world as it is

- Waag’s first fifteen years

From the windowsill of her office overlooking the Nieuwmarkt, Waag’s president, Marleen Stikker, picks up a glass jar labelled with a question mark. As she tilts it, a white sediment drifts through the pink liquid inside.

“It’s hybrid DNA, so it’s not clear what it is,” she says. The jar is an artefact of a recent public project conducted by artist-in-residence Adam Zaretsky on the Nieuwmarkt. Making your own new genetic material is easy, Marleen says. “You take all kinds of different materials, like food and spit, and then you have a mixture of different DNA. You put it in a blender, and then you put lens solution in, and there’s some stuff you add to it, and then you mix it again.”

It’s an apt metaphor for Waag itself. Since 1994, the organisation has been chucking together technology, art, education and the social good, mixing it all up, and giving life to new media forms.

But you can’t make the stuff in that jar grow into a monster, right? “Well, it depends,” says Marleen. “The next step is, what do you do with it? So in his lab, Adam asks people, what shall we do with it now?”

That’s when you hope the jar is in the hands of someone with a conscience. And it makes all the difference that Waag has always been in the hands of benign Dr Frankensteins. From day one, their aim has been to use technology to change society in a positive way.

The digital frontier

Involved in the theatre in the early 1990s, Marleen was interested in “playing with media and technology and seeing how it influenced expression,” she says. As she was organising arts happenings like the ‘live magazines’ at De Balie, Caroline Nevejan at nearby Paradiso, responsible for events like the Galactic Hacker Party, was becoming concerned with technology’s relationship to social issues. “This was a very good combination,” Marleen says.

Marleen had been working on the 1994 launch of De Digitale Stad (the Digital City), a subscription-free ISP and Web community that linked city residents and public institutions. “For a lot of people, it was the first access to the Internet – for organisations, newspapers, city councils, as well as individuals,” Marleen says. “The Digital City is still the DNA of Waag.”

For their grand experiment, the Digital City founders brought together hackers, the arts community, and technically minded media types. “This combination of people, in their nature, doesn’t take the world as it is,” says Marleen. “They’re looking for alternatives, for a better world, or another possible world. Bringing these people together was very fertile. There was an interesting mix of backgrounds, skills and temperaments. I felt that it was important to create an environment for that that would be more sustainable.”

She and Caroline decided to found a new ‘media lab’. They took the medialab at Massachusetts Institute of Technology as a partial model. But they wanted theirs to involve the community. “We were very strong in believing that this lab should be in the public sphere – a sociable lab,” Marleen says. “That’s why we called it a society. It was within society. It was about that relationship.”

Before 1994 was out, the two women had started the Society for Old and New Media. By old media they meant “events, and gatherings, and real-life situations,” Marleen says. “We didn’t want to only be in cyberspace. Some stuff you do in real life, with real people, and you use the virtual as one stage in it.”

Open access

That meant they needed housing. Winning a ‘beauty contest’ competition enabled Waag to move into the iconic medieval gatehouse in 1996. By then, the core team included people like media theorist Geert Lovink, designer Mieke Gerritzen, artist Janine Huizenga, designer/engineer Michael van Eeden en research fellows Patrice Riemens and David Garcia. The organisation received financial support from Paradiso, De Balie and Rabobank.

The central mission in the early days was to make Internet accessible. That resulted in the Reading Table of Old and New Media. Equipped with magazines, newspapers, and special designed interfaces for Internet access, it was made available to the public in the Waag’s restaurant in 1996. It won the Rotterdam Design Prize the following year.

“We did our first venture around the Reading Table,” Marleen says, “because people kept asking us if we could make another one.” They formed a company with an investor, but it failed. It was the late 1990s, and public Internet access wasn’t yet a craze. The table was ahead of its time.

So was another 1996 project, Transparent Amsterdam. “I guess it was the first GIS application on the Internet”, Marleen says. This online map was based on the work of the architecture information centre ARCAM. ARCAM had made a giant physical map of the region showing planned infrastructural developments. “We wanted to see if we could make it accessible online. It was one of the first citizens research projects that made data public in order to influence politics. There was no geo information online. So we went to Geodan, and asked if we could publish their GIS database on the Internet. The database of all the projects ARCAM had collected was presented as layers on top of the map. You could find different views on housing, roads, schools, everything that was planned. And we made a tool for people to discuss them.”

Activists, artists and hackers

It was still the age of 14.4K dialup modems. The organisation – at that time known as Waag for Old and New Media – was establishing itself as a pioneer. “Nowadays we do a lot of locative projects, city projects, and with gaming like the new mobile software platform 7scenes,” Marleen says. “When we looked into our archive, we realised it had already started in 1996.”

Waag was an active partner in the international tactical Media Network and where part of the Hybrid Workspace, a 100-day workshop at 1997’s Documenta X in Germany at which activists, artists and programmers worked together on interventions. Waag’s We Want Bandwidth campaign became legendary.

Back at the Waag itself several live arts events took place. The Killer Application is People Club (Now KillerTV), a programme of lectures, discussions and presentations held in the Theatrum Anatomicum and streamed online, began in 1997 and is still running today.

But Waag was doing plenty of less glamorous good works too: it had begun to turn its attention to ways technology could help children and the elderly, true to its mission of social improvement. It founded the Gouden @penstaart children’s website awards and held the Ouderenworkshop, at which senior citizens and young designers and developers brainstormed ways technology could help enhance people’s lives in old age. Their conclusions were used a few years later in the development of the Storytable.

Behind the scenes, more technical research was also proceeding apace. The KeyStroke (later KeyWorx) client/server software platform for media and performing artists went into development. A distributed application framework, KeyStroke made it possible for performers to create images, sounds and text live in a shared online environment. It was yet another project with legs: over the years, various versions would prove useful in numerous projects in which people where facilitated to collaboratively work or play realtime.

Locative programme

As the new century began, Waag stepped out onto a wider stage, joining forces with Delhi’s Sarai Media Lab to do joint work on political issues around new technology. Later, Brazil and New York joined the overseas connections. Together, the organisations would publish readers, organise conferences and develop software.

Meanwhile, Waag was expanding its locative work. In 2002, it embarked on one of its achievements that attracted international attention: Amsterdam RealTime. Citizens were given GPS-equipped PDAs to carry for one week; their movements were tracked and rendered in realtime on a public screen at the municipal archives. The participants by their movements created a personal map of the city. They even adapted their routes, as others could see the results of their movements.

Underneath it all, the KeyWorx software platform was quietly humming. Amsterdam RealTime was built on it, as were two very different projects: ScratchWorx, a simple DJ/VJ console designed to get schoolchildren interested in computers, film, image and sound, and the Animatiemachine, an installation kids could use to make animated films.

Waag began to develop more educational projects. One in particular, the 2002 art-history adventure game Demi Dubbel, was serious gaming avant la lettre. Incorporating activities like theatre and painting into an online game, it was played in numerous Dutch schools, and even between groups of kids in the Netherlands and the United States. “In a way it established the whole concept of creative learning and using adventures and game principles in learning processes,” Marleen says.

The focus was to make technology useful to the elderly with multimedia tables – a Waag concept that was coming into its own at last. A local retirement home wanted to offer their residents Internet connection. From conversations with the residents Waag learned that the real need was to do something about their loneliness. Using input from residents, the Storytable was conceived, a kind of jukebox with historical audio and visual fragments which allowed users to add their own oral narratives. These days, about 75 tables are in use around the Netherlands. Two similar projects, De Wisselkabinet and Het Register van de Dag van Gister, continued the Storytable’s evolution. ‘Media furniture’s’ time had come.

Over the years, the Waag’s work for the elderly has expanded into projects for the wider healthcare field. For example Pilotus, a software programme that allows mentally disabled people and their families and carers to communicate via images, voice and pictographs.

Play gets serious

In the first decade of the century, Waag designed adventure games for heritage institutions like the Drents Archief (the Drenthe provincial archive) and Haarlem’s Teylers Museum. But then educational gaming went mobile and really took off.

With local schools, Waag developed the mobile game Frequency 1550 in 2005 to teach teenagers 16th-century Amsterdam history. Players walked through the city with GPS-equipped phones, carrying out location-specific tasks: making videos, snapshots and audio files. Game elements were added like the possibility to hide in the city, place bombs and take away points from others.

The kids and teachers loved the game, it drew national media attention, and a university study found it enhanced learning. “Frequency 1550 was an essential step, in the development of our locative and gaming research but also from the point of view of how you organise interesting learning environments”, Marleen says.

Creative research

Waag plays an important role in organising an infrastructure for the Dutch creative industries. It helped to convince the government to name the creative industries as one of the country’s key innovative sectors. It was also involved in founding IIP Create, the ICT Innovation Platform for the creative industries. And in 2004 it co-founded Creative Commons Netherlands, which promotes the Creative Commons content licensing system, with Nederland Kennisland and the Institute for Information Law.

One of main issues in the creative industries is bringing creative ideas into practice. How to can creativity become sustainable products and services? This was a question for Waag’s own research and development, but the organisation was also approached by independent creatives for help. To foster this process better, Media Guild was established, an incubator for starting creative entrepreneurs.

Waag is a pioneer in creative research and the collaboration between art and science. It participates in national research programmes, like MultimediaN and GATE. GATE is a research programme on serious gaming. One theme of MultimediaN is collaborative creation and multimodal interfaces.

That created the context for the two year Connected! research programme into collaborative, multi-locational performance art.Projects included installations, an artists-in-residence programme, and the Sentient Creatures lecture series. There were also the weekly Anatomic events, in which artists in different locations performed ‘together’ over the Internet. A report of this research was published with the publication Connected! LiveArt.

From its start, Waag has been connected to the research infrastructure in The Netherlands. Together with Surfnet it founded Culture Grid, an Internet provider for cultural organisations. The cooperation also sparked CineGrid, an international research initiative to enable ultra-high performance digital media over advanced networks.

By the middle of the decade, Waag had gotten too big for its castle on the Nieuwmarkt. With the communications and events agency Cultuurfabriek, it started to look for a new building. Pakhuis de Zwijger, a warehouse in the Eastern Docklands, was being redeveloped for the creative industries. Waag housed its new branches like Media Guild, Culture Grid and Creative Learning Lab, the educational section, at this new space.

The same year PICNIC was founded, an annual media and technology conference. Waag is contributor to PICNIC’s organisation and programming.

It’s a meeting place for people from various disciplines (art, science, business and society) that want to make a practical contribution to the design of our future.

Waag is not only active in the virtual world but operates more often in the tangible one. “In 1994, we were pioneers in discovering and shaping cyberspace,” Marleen says. “And now cyberspace has come into the real world, and our orientation is going back to physical space.” An example of this is Scottie, a vaguely doll-shaped wireless object for children in hospital to use to communicate with faraway loved ones. The two users manipulate light, warmth and vibration values, which are transmitted between the objects via wireless Internet. Scottie, still under development, “is an important project,” says Marleen, not least because it signified a move toward hardware, “to make technology tangible again.” Marleen estimates this as a valuable research into emotional computing. It’s an inspiration for many and the ‘remote cuddling’ is now being tried out at the AMC hospital in Amsterdam.

Open design

In the same line as open source and open design, Waag in 2007 took the next step towards open hardware with the Fablab Amsterdam at Pakhuis De Zwijger. It uses a standardized open-hardware desktop manufacturing facility for workshops and rapid prototyping. Members of the public can also use it by arrangement.

One of the main events in 2009 was the (Un)limited Design Contest, an open-design competition co-organised with Dutch design foundation Premsela, other Fablabs and Creative Commons Netherlands. Anyone could enter by making his or her own product at a Fablab.

Open genome

In the programme called Utopian Practices: Art, Science and Design REunited Waag works together with the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences’ Virtual Knowledge Studio and Leiden University’s Arts and Genomics Centre at a new challenge. Is it finally time to reunite the Sciences with the Arts? How can we (re)combine the works of artists, designers and scientists, and what value would it add?

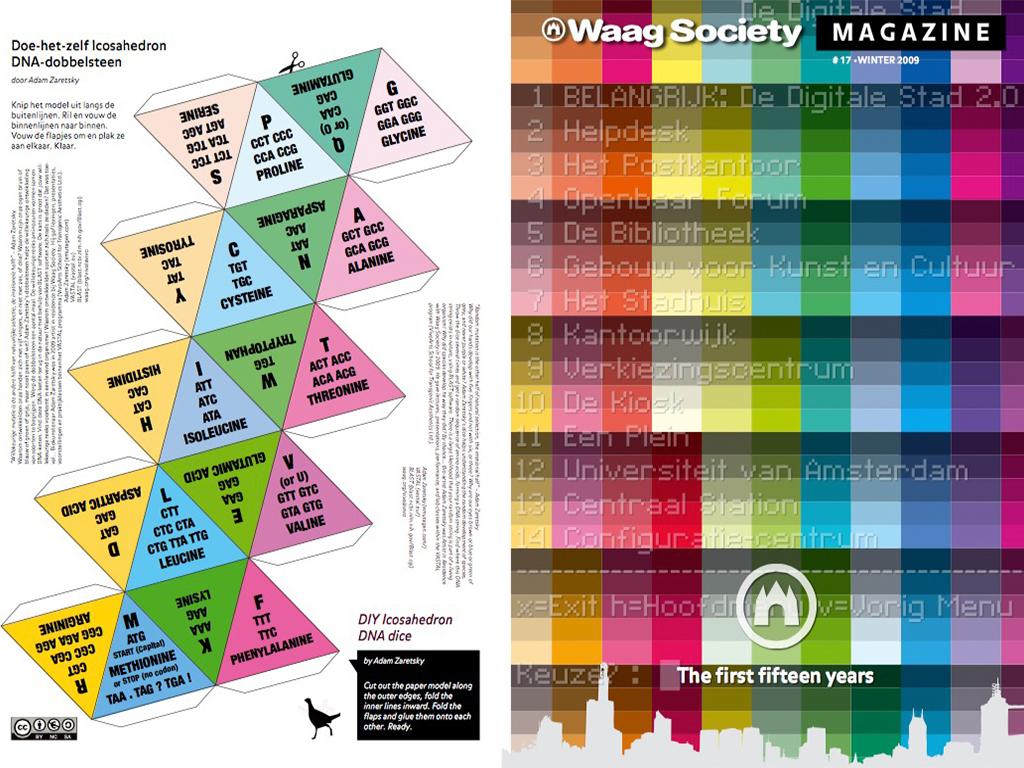

As a part of this programme the artist-in-residency of Adam Zaretsky is set up as a ‘temporary research and education institute’, the VivoArts School for Transgenic Aesthetics Ltd. (VASTAL). One element is a wet lab, a mobile set of machines and tools where artists and members of the public can create biotech artworks, such as sculptures of plant matter and human tissue cultures.

We’re back to the jar with the question mark and the hybrid DNA inside. “The workshop was on the square, at the organic market,” says Marleen. “It was funny, because those people are really afraid of biogenetics.”

She likens these new explorations to Waag’s pioneering work on the cyberspace frontier back in the early 1990s. “We’re now part of ‘The Internet of Things’, of technology going into society, often in an invisible form and with large consequences. The same will happen with biotechnology. Just like 15 years ago, we want to bring this knowledge into the public sphere, together with artists and designers. There’s no telling yet what the effects of user-generated DNA will be.”

Back in 1994, Marleen and co. knew that new media would have huge effects on the world, even if they couldn’t predict exactly what the details of those effects would be. “After all, it’s not as if they’re a foregone conclusion,” she says. “Essential is, that you have to be part of the design. It’s not an act of God; it’s human activity.”

“This is also the background for the sustainability projects that we already started back in 1996 with the EcoGames competition. The most recent research project Powermapping showed the feasibility of decentral energy production on the roofs of the city. With a project like Ecomap, citizens research plays important role.

Creative learning

As the first decade draw to a close, several long-running activities at Waag have become institutionalised. The Creative Learning Lab was set up in Pakhuis de Zwijger as a platform for both the educational world and the creative industries. Teachers and school administrators are trained to use digital technology in lessons and pupils are teached about creativity, technology and cooperation. An annual peak is at PICNIC YOUNG, where about a thousand teachers and pupils come together.

And Frequency 1550’s success led to the Games Atelier, a two-year programme of activities that helped pupils and teachers to make their own location-based games.

The future

Soon, Waag will take locative games public. 7scenes, a new software platform for mobile games and services, is already being used by cultural organisations for projects like De Tijdmachine (Time Machine), a driving tour of the Noord-Holland polders that takes the form of an audio play. The 7scenes platform will soon be made publicly available.

Another promising initiative for the future is THNK, a post-graduate academy in the field of creativity and technology, in which Waag cooperates with the University of Amsterdam and the VU University.

Part of this should be a permanent wet lab. What new life forms might be unleashed there? We’ll see. Whatever happens, Waag will be questioning the process all along the way, with the social good in mind, in the old hacker/artist/activist spirit that’s made it what it is down the years. It’s what they do. “We open up Pandora’s boxes,” says Marleen, “and then we want to do something with the knowledge that comes out.”

Published as magazine to commemorate our 15th anniversary in December 2009.