Designer Mary Farwy already created outstanding work during this year’s BioHack Academy 2022, together with designer and friend Michel Barchini. Now, Farwy has been selected for Waag’s residency program as part of the 3Package Deal 2022. She follows in the footsteps of Yara Said (2021) en Adriana Knouf (2020). A talk on the architecture of well-being and mud batteries.

Hi Mary, congratulations on being selected for the residency program! Where were you when you heard the news?

I woke up at home in the morning when I saw the e-mail. I was really glad it paid off, because applying for funds is very competitive.

What is your educational background?

I started off studying architecture in Syria, which was a very technical, traditional kind of architecture. Then, I went to Italy to study architecture at the Politecnico di Torino for three years. When I graduated, it left me feeling unsatisfied because traditional architecture is quite limiting in the way you design.

Mainstream architecture is very focused on the functionality of spaces rather than other aspects of design, like the emotional aspects or the human psyche. I felt that I wanted to do something with more fluidity at the heart of its discipline. That’s why I did my Masters at the Royal Academy of the Art (KABK) in The Hague. The programme is called Interior Architecture, but personally, I don’t think it has much to do with interior architecture at all. I would rather call it social or contextual design. My take of it was more intersectional, focusing on political, social layers and then translating that to space. My practice shifted from designing the space itself, into using the space as a medium.

How does the social-political part connect to architecture?

Most people think of architectural buildings when they think of architecture. I think architecture should be more open and merged. Our bodies for example also have an architectural structure. Architecture shouldn’t be distant, creating walls that separate our bodies from physical spaces. Rather, it should dismantle the boundaries between the architecture of your body and the space around it. How you design spaces, affects your experiences and senses.

Maybe it’s good to give an example. The first work that sparked this interest in me, was by Arakawa and Gins. They are Japanese-American landscape artists from the seventies who basically designed spaces that strengthen your immune system. Arakawa and Gins base their work on the powers of our perception and on how we perceive our environment. And then they integrate these understandings in the houses they create. The house’s design encourages you to move in a certain way, that would eventually improve your immune system. When I was studying their work four years ago, my thinking changed in regards to the relation between bodies and spaces.

Which themes are you currently most interested in?

That would be three themes: inherited trauma, hacking the supply chain and epigenetics. The bigger umbrella is the architecture of well-being. How can you for example mobilize spaces to help deal with trauma?

You would have to explain the concept of ‘epigenetics’ to me.

Epigenetics is a science that studies the relation between your genes and life experiences. This means that any kind of heavy emotional experience have a consequence on your biology. Epigenetics studies how experiences do alterations in your genes. I find this very interesting, because we might think we are born with our genes, while they are also affected by experiences.

It makes me think of the bestseller The Body Keeps the Score by psychiatrist Bessel van der Kolk. He focuses on the effects of trauma and what traumatic experiences do to your body. Does this interest in epigenetics and inherited trauma come from a personal situation?

You pressed the right button. The personal was the beginning of a research that led to my work Making Dying Illegal, even though my personal experience wasn’t portrayed directly in the final publication and video. I investigated chronic stress and the biological effects for alienated figures in society. Because in my experience, there’s such a loaded amount of victimisation and stigmatisation for people with a war experience. I think it’s important to approach it more as an experience instead of an identity for these people. It frames you, and I didn’t like that. I wanted to understand why this happens and how can you hack it.

In the video [watch Making Dying Illegal], I wanted to stay away from the imagery of brutal war images that seems to focus more on the tragedy of the event itself, like you see so often. Yes, war is what happened, but I’m more interested in what can you do with the experience and how to understand it.

You finished the BioHack Academy at Waag, this year. Did you gain specific skills or knowledge that help in your current practice?

It all started when I graduated in 2020 on an alternative toilet system that doesn’t only focus on the flushing, but also on the psyche. Already, this project intersected science and technology. But it was very trapped in an abstract and theoretical frame, because I didn’t have the technical skills when it comes to biotechnologies. I felt like I wanted to gain those skills. That’s why I did the BioHack Academy.

You learn about the technical hardware layer of labs and how to work in them, and to work with bacteria or grow other living organisms to learning to digitally design DNA. It turned out it was exactly what I needed for my work and very beneficial experience for later, because I’ve been using so much of the technologies I learned from the Academy.

Like the work I did with designer Michel Barchini under the name of Hackitects, a concept club work. For their Summer School, we collaborated with Hackers and Designers and gave workshops on how to make mud batteries to generate electricity. These works all sparked after the BioHack Academy.

What work did you create during the BioHack Academy?

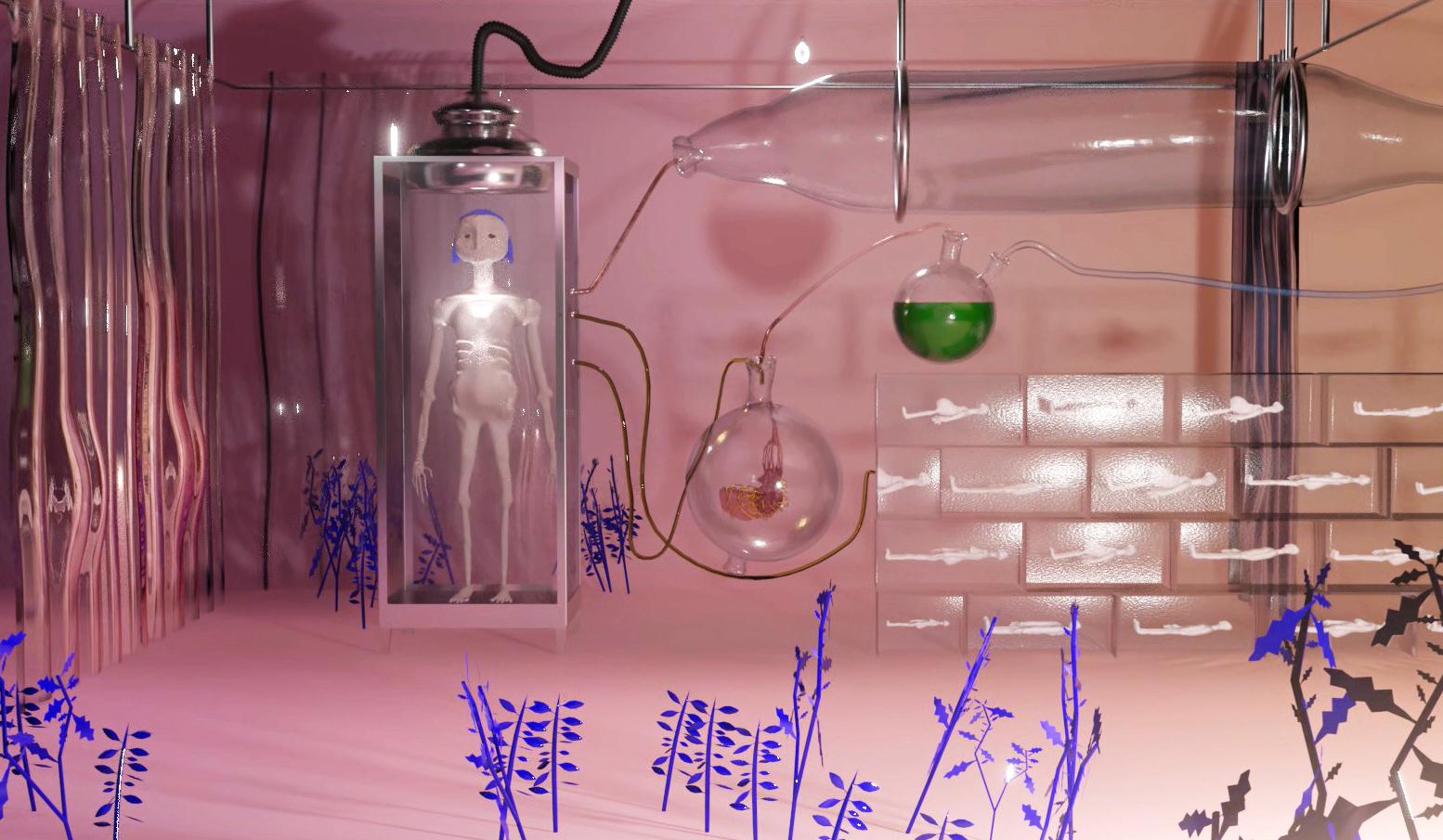

This brings me to the third theme I’m interested in: ways to hack the production and supply chain. The work I created during the Academy with Michel is called Cocobiota. In the Open Wetlab, we experimented with growing cacao cells, asking how lab-grown cacao would affect the supply chain if you move away from the tree plantations, deforestation, the bad effects of labour and child labour, and the colonial history that is linked to cacao. It is our way of hacking the cacao supply chain. We also wanted to infuse lab grown cacao with oxytocin and endorphins, stretching the limits of altering moods and feelings of comfort.

How does Cocobiota link to the architecture of well-being?

The cacao tree grows in the forest, which eventually is a space. There’s so much abuse affecting the space and the cacao tree itself. According to estimations, the cacao tree will go extinct within twenty to thirty years, because the harvesting is done in a higher pace than what the land can provide. Everything can be linked back to architecture, because we’re hosted in spaces all the time.

I remember that the work had a speculative part to it, right?

Exactly. And since that moment, I don’t want to use the word speculative anymore. I want to reform and change the work and to push it more in the commercial aspect. Beforehand, I was more into writing and video-making. But now, I want to create a sense of impact and to be able to see the results. That’s why I’m also giving more practical workshops on mud batteries for children and students.

Would it be felt more impactful to you, if you could change the commercial supply chain of cacao?

It’s for the long run, it would be a big project and much more collaborations would be needed, but yes. We also chose cacao because when you don’t need to introduce cacao and so many people love it. I think pushing the work more into food, or electricity from batteries, would make Cocobiota more approachable.

When I started reflecting on my earlier work, it seemed so much within an academic, intellectual bubble and mostly for people who were interested in specific topics like bio-design. The word epigenetics doesn’t directly relate to many people. For instance, when I told my mom about my research on epigenetics, she didn’t immediately understand it. I felt that I wanted to be able to create works that I can explain to my mom in two sentences. I feel it’s very challenging to always do so, but it’s one of my goals of this year.