It is 15 January 2016, and about 40 students gather in our Anatomical Theatre. They’re following the course History of Digital Cultures at the UvA, where they are digging up the old remains of De Digitale Stad (the digital city, DDS). The students have been digging up, reading and modifying code for two weeks now, and today they get to present their preliminary findings to each other and to the former ‘mayor’ of the DDS: Waag director Marleen Stikker. Oh, and also: today is DDS’s birthday. It was founded on 15 January 1994, so it turns 22 today.

The digital city was the first public Internet space in The Netherlands. When it was founded, Internet technology was used solely in the domain of academics and the military. There was no commercial Internet yet, and the DDS was an exploration of what could be possible if people could communicate via computers. It was the public appropriation of a brand new technology. The website existed until 2001 and had many users based in Amsterdam.

Unfortunately, DDS hasn’t been archived in a durable and sustainable way (yet). Right now, it takes quite some programming expertise to access and review the old data. But that’s exactly what these students have. They have defined a wide variety of historical research questions and are now using DDS-data to answer them. In just two weeks, groups have managed to find different features of the city and even to ‘make it work’ again. But more importantly, they are using the data to answer broader questions about the design and the use of the early Internet.

It is very exciting to hear how the Internet in 1994 was immediately used for anything we know now too. One group of students is studying online dating: people trying to meet each other (or even chat!) in the DDS. Old chats are being dug up, the development of romances can be traced (with regards for privacy concerns, of course). Another group is mapping how the DDS became more commercial over the years and how that development was related to the social and technological culture of that time. Politicians were present; the DDS strongly supported the idea of politicians meeting regular people online and sharing political discussions. The metaphor of the city, including a metro, cafes and squares is being analysed. Because the DDS stood firmly for an open and free web for all, they were very reluctant to censor any content or ban any users. One of the groups of students is now reconstructing how the DDS dealt with anonymity and the free and open sharing of content, which was sometimes controversial.

And then, in the coffee break, students fire up the original DDS chess machine and start to play a chess game (usernames: aboutaleb vs eberhard) in the old interface. They even found some old chess robots, showing early examples of artificial intelligence.

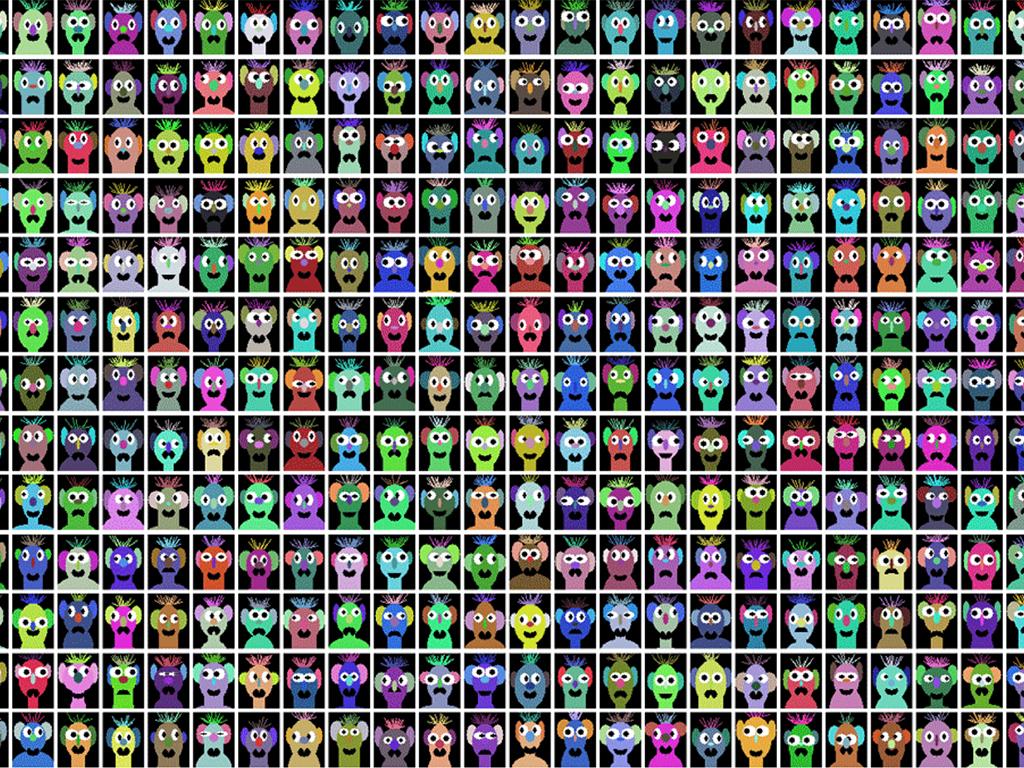

Of course, issues of originality and ‘making it work again’ are complex. Anything working on a modern computer today has actually been modified from its original state in order to work and become visual and responsive again. It could be argued that this modification means you lose the original. But if you are interested in seeing old algorithms in new html, check out the Avatar generator that was part of the DDS experience. Via the Avatar generator you can create your own and unique avatar once again.

Hopefully we will be able to do much more of this web-archaeology in the future, when Waag, UvA, Beeld en Geluid and the Amsterdam Museum collaborate to archive the DDS in a sustainable way and disclose the data for a wide audience to see. In our view, this digital heritage is just as important as any other building, city hall or canal in our physical public space. It deserves archiving and studying. Good to see that these talented students are getting started already.