Planet B builds on the speculative idea of a second planet. Given such an opportunity, what could we do better? How might we populate planet B in ways that are sustainable and fair for all? A thought experiment with promising outcomes.

With an interdisciplinary group of people, we discussed and designed the contours of planet B at our outpost at Amsterdam Science Park. A central question is focused on the role of technology on planet B: what does it take to use technology in fair and equal ways? A question relevant from the level of the city, up to space.

Humans in space: a confrontation with our limits

In line with the theme of planet B, space functions as an exploration ground for life beyond planet earth. But thinking about life on other planets forces us to reconsider what it means to be human. And it exposes our longing to expand, and to be known.

Think of the Voyager Golden Records, for example. These records, sent to outer space on board of a satellite, stored sounds and images that ‘define’ human beings as an explanation for the extraterrestrial forms of life it might encounter. With a collection of music and greetings in 55 languages, the digital collection of humanity exposes that we want to be known, and expect that others want to know us too.

Space also confronts us with the limitations of being human, for example because of travel distances. As a consequence, the relation between humans and technology changes. From imagined luxury travels with reusable rockets to local, scientific research with the Mars Rover: in our discovery of new territory and new forms of life, human and technology become involved in new ways. As artist Antti Tenetz argues, we might need to think of AI systems as our companions for space travels.

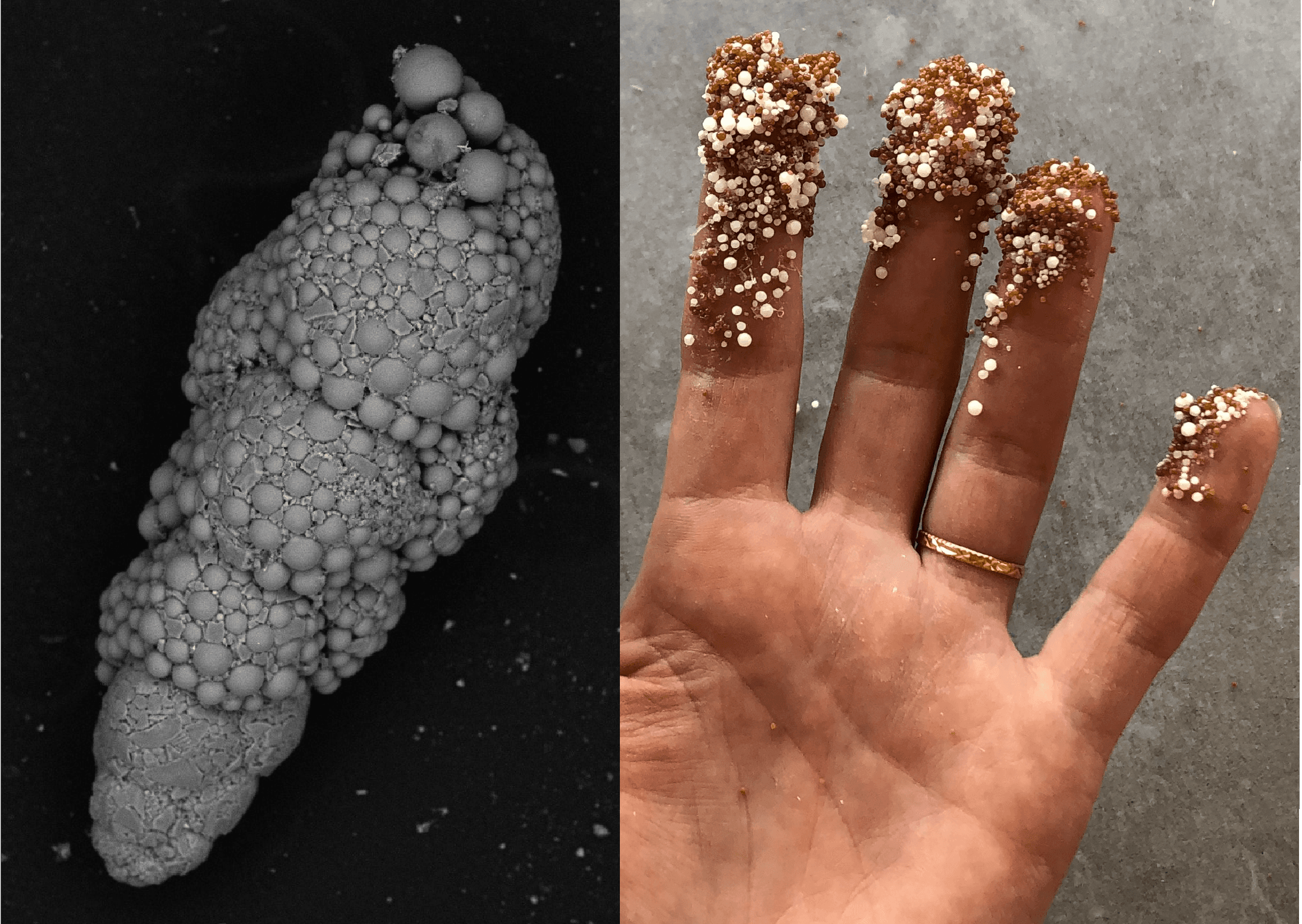

Thinking about such relationships, Antti’s work Periphelion shows speculative images of outer space, creating eery cross-overs between existing pictures and bacteria. Is this what bacterias dream of?

Antti and other artists shared their critical perspectives on human space explorations during the Supre:organism exhibition at Kunstfort bij Vijfhuizen. They reflected on what it means to be human in outerspace and show us how our space travels are the result of a human-centered way of thinking, that can be regarded as colonial and elitist. Are there other ways to relate to space?

Online visions of the physical city

Questions of inclusion and exclusion have also come up within planet B in local settings. As artist in residence, Sjoerd ter Borg, and the rest of his collective Aesthetics of Exclusion, studied processes of gentrification. Their installations shed light on the aesthetics of gentrification. How does gentrification become visible?

In the Tinder-inspired Streetswipe installation, users can judge whether they think a storefront is gentrified or not, opening up a discussion about what gentrification can mean to different groups of people. Their use of machine learning techniques and image archives enables Aesthetics of Exclusion to create a timeline of city development. Switching between old and new, between past and present, they urge us to think about the future of cities.

What started out as a project in which technology is used as tool, the work of the collective has become a critical reflection on technology itself. Technologies might be the tools for research, the usage has effects on the project itself and on whoever is using it. In the words of James Bridle: computation “constructs a future that best fits its parameters”. Whether it’s about city life, or space explorations.

Reflecting on technology

In the AI Culture Lab, the first expedition of planet B, artificial intelligence is a central focus. Both as tool - how can we use it for cultural good? - and as subject of reflection. The problematic view of AI as an international race - a competition we can win or lose if we do not innovate quickly enough - urges us to think about when and how we want to employ certain technologies.

With AI, processes of categorisation are inherently tied to the functioning of these systems. But what is represented and what is not? As researcher Flavia Dzodan points out, classifying is an act of power with a long and problematic history. Who gets to classify and who is being classified?

As Tom Demeyer argues in his essay AI in Culture & Society, it is hard to distinguish necessary classification from undesirable bias. But while categorisation cannot be avoided, we can work on making more complete and inclusive datasets, that are not western, or urban centric. In the words of Flavia, we can ask: do the data sets represent the world at large, or does it represent merely the world the maker thought was worth including?

Artificial intelligence is something completely different than human intelligence, which has consequences for the tasks that AI can or cannot perform. The term AI is overly used, and describes a messy field sometimes indistinguishable from other forms of technology. But what AI can help us to do, as Tom argues, is “‘freeze’ a small section of our culture and lift it out into a model, enabling us to prod, probe and study that little bit of our existence in ways that we have never before been able to”.

Whether we talk about space, the city, or technology in general: with planet B we need to explore how technology can be used in fair and inclusive forms. So, we look for new forms of power with decentralised bots, find out how AI can help us with environmental challenges and retrace what networks are in a traditional sense, to constantly demystify what technology is and what it can do.

A big mission, that we will continue in the upcoming months. Planet B is not real yet, but these lessons have gotten us one step closer to our launch.