With envy, some have watched Asian countries, that use digital tracking and tracing on their inhabitants in order to battle corona. These countries usually don't have to deal with privacy and can make maximal use of their infrastructure for surveillance. But is it really necessary to weigh these two things: do we have to give in on privacy in order to battle the corona virus? That's what we would think, considering the director of the Dutch authority for personal data (Autoriteit Persoonsgegevens), when he states he won't be strict towards initiatives for battling corona right now. One would think that this is exactly what he was appointed for. It was his job to make visible that the antithesis is false in the first place: privacy and the effective combat of corona virus are not each others' opposites.

'Privacy and the effective combat of corona virus are not each other's opposites.'

There are many ways in which people's data tracks can be mapped. Our mobile phones are central in this quest. We carry our phones voluntarily and are with them for most of the day and the night. Our locations are tracked continuously as part of the key functions of our phones: telecom providers need to be able to route conversations towards the location of you and your phone. Locations are related to the UMTS "mast" to which your phone is logged in to. The accuracy is limited, depending on if you are in a city or not. The provider then saves these data, compliant with the law. Investigative services make use of these data a lot.

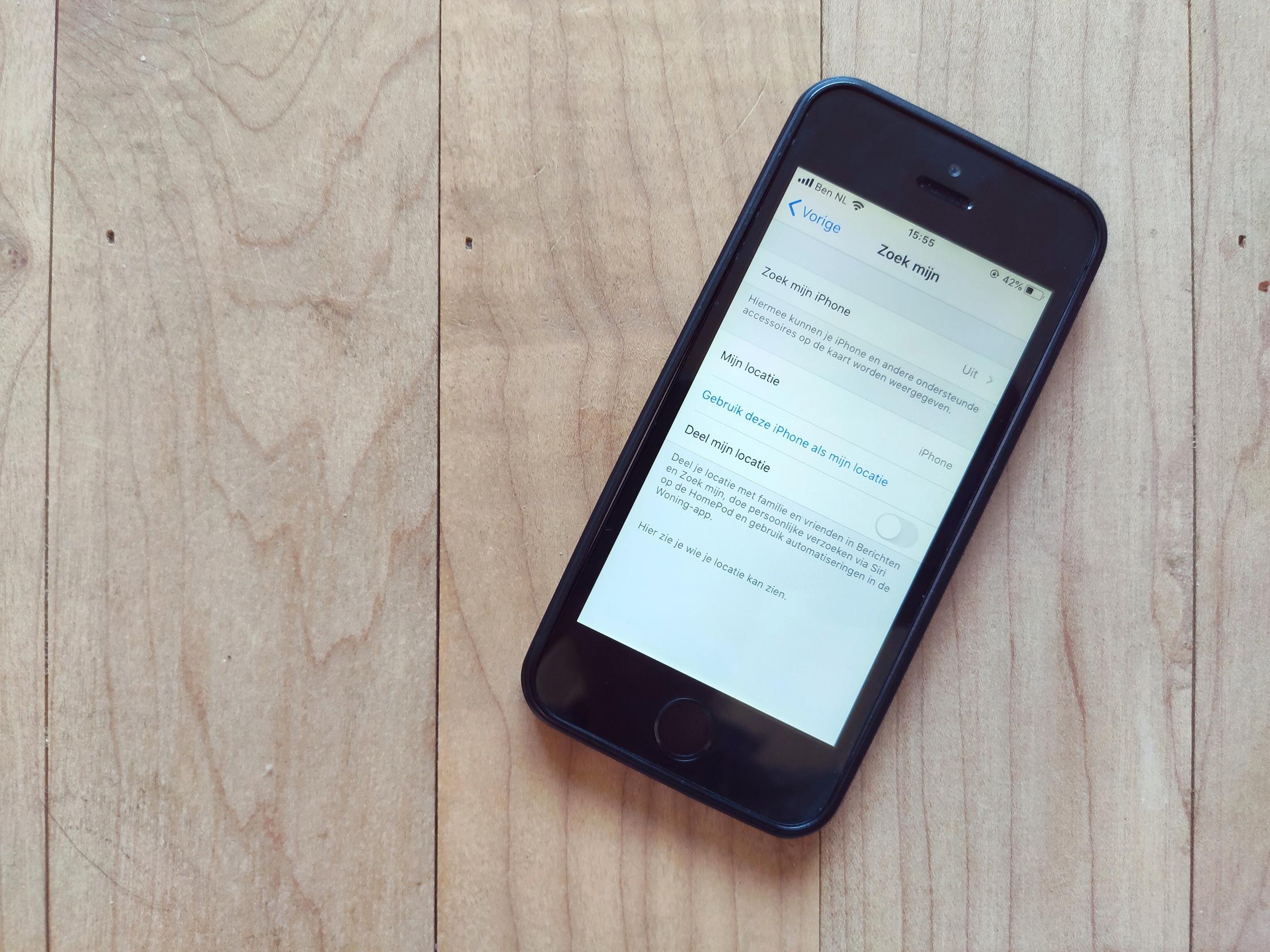

Next to this, most phones have 'location services' on them. With these services, the UMTS 'masts' are combined with satellites for GPS navigation and locally visible WiFi networks. This then leads to a much more accurate determination of position, close to a few meters. If you have these location services switched on on your phone, your location data are sent periodically to Google, Apple and possibly the suppliers of specific apps you installed on your phone. The fact that these companies save your location data is a violation of privacy in itself. Still, without shame, Google publishes these data when relating it to the increase and decrease of visitors in certain places. They publish the data after it has been cumulated and anonymized, so it can not be traced back to the individual.

With the methods mentioned above, one can track if people have stayed at home or if they have made a possibly illegal visit to a park or beach. It's a powerful tool for a state that, from a central position, wants to punish their inhabitants for unlawfully changing locations. But it doesn't provide information to people who themselves want to consider if they have been close to someone who carries the virus. Singapore was one of the first countries to implement a so-called contact tracing through the TraceTogether app, which works via Bluetooth. Instead of registering the absolute location of the phone, the app registers the close proximity of another phone with the same Bluetooth app. Contact tracing in this sense thus means that the app can track with whom you've had physical contact. Every phone has its own unique Bluetooth ID or mac address. The app can save the encounter between the IDs and alarms you whenever you've been in contact with someone who was then infected. This allows you to self-quarantine. There's a lot more accuracy in this, even if not all circumstances are optimal.

Of course, all of this leads to a huge dilemma. The Bluetooth ID is personal data in GDPR law, which means it can't just be saved. The database this would create, would serve as an enormous hotspot for privacy - even more so, as the premise for the success of the app is the mass adoption and broad use among the people. If this technology is used without thinking it through properly, privacy will suffer as a consequence.

'If this technology is used without thinking it through properly, privacy will suffer as a consequence.'

It's fortunate that techniques exist to make privacy-friendly the principle of the approach mentioned above. Suppose that every moment of contact is not saved centrally, but on both phones. And suppose that phone A saves the time and the contact ID, that is different for every contact, on phone B by encryption, and vice versa. The saved data is then unreadable, because of its encryption. Theoretically, the only person to read this data is then the original owner of these data.

Whenever the owner of phone A would be tested positive (by a healthcare professional, and only then), the app could register this centrally by publishing the key for decryption of the app on phone A. With this key, everyone who uses the feature can check if they have been in contact with the person who published his key (this would take place automatically in the background of the app), and take the necessary measures.

This means we can trace contacts in a way that is privacy friendly. The approach we mentioned is now being developed by various groups, such as privatetracer.org.

'In a time of crisis, we should not hollow out our public values and human rights: we should fortify them.'

There are a few important sidenotes to make with this approach. At this moment, there is no scientifical evidence available that states that registration of close proximity is an actual way of mapping the spread of corona virus. Singapore had to take additional measures, as the mapping of contacts wasn't effective enough. Next to this, a very broad adoption of the app is necessary in order to have a chance at getting results. That's one of the main reasons why people need to trust the app. At this moment, there are multiple initiatives being developed. There's danger in the fact that these developers aren't working together. It's now of great importance that we make a decision fast and collectively - a decision that respects privacy. The European Commission also called for this. In a time of crisis, we should not hollow out our public values and human rights: we should fortify them.

Background information:

- Private Tracer

- Pan-European Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing

- COVID Defender - Future Lab

- Decentralized Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing

- Disposable Identities for Health Crisis

- 10 requirements for the evaluation of "Contact Tracing" apps (CCC)

- Jaromil (Dyne) - Decentralized Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing crypto made easy

- Covid Watch - protect their communities from COVID-19 without sacrificing their personal privacy